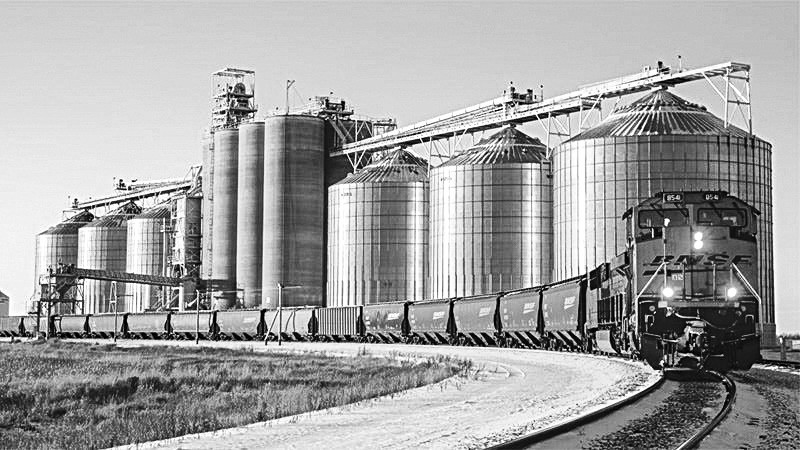

Each railroad reports “unfilled orders” referring to the number of cars a shipper, such as a grain elevator, ordered but did not receive. Between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, the number of unfilled orders jumped from 93,000 to 137,000 — a 47% increase. Photo by BNSF

WASHINGTON — The U.S. railway system, long considered a cost-effective and reliable way to get agricultural inputs and commodities to their destination, are not immune to the post-pandemic supply chain logistical challenges and service disruption.

So much so that Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway (BNSF) recently acknowledged that their level of service is not where it needs to be.

In a letter to the National Grain and Feed Association and the National Surface Transportation Board, BNSF shared details of their service restoration plan focused on crew and locomotive availability as well as rail car inventory management.

According to American Farm Bureau Federation Economist Daniel Munch, improvements can’t come quick enough, as there’s a dramatic increase in unfilled rail car orders and escalating shipping costs.

“Many of the issues we’ve been hearing about in trucking and ocean freight also contribute to rail service disruptions. There’s a significant shortage in rail crew labor, which is expected to be the largest contributor,” Munch said.

The impact to agriculture is magnified based on the sheer volume of freight normally moved via rail, said Munch, with U.S. railways accounting for nearly 28% of freight movement, second only to trucks.

Roughly 94% of the revenue generated by the U.S. rail system belongs to just seven Class-I railroad-operating firms defined as having annual carrier operating revenue of $900 million or more.

In addition to BNSF, Canadian National Railway (CN), Canadian Pacific Railway (CP), CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS), Norfolk Southern Railway (NS) and Union Pacific Railroad (UP) are included in the Class-I designation.

Each railroad reports “unfilled orders” referring to the number of cars a shipper, such as a grain elevator, ordered but did not receive. Between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, the number of unfilled orders jumped from 93,000 to 137,000 — a 47% increase.

BNSF reported the largest jump — nearly 50,000 unfilled orders — followed by CP with an additional 14,500 unfilled orders. More than half of those unfilled orders were 11 days or more overdue, revealing the severity of disruption for some shippers.

Between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, the number of 11-plus days overdue orders jumped 39,000 or 107%. By percentage and numerical increase, BNSF saw the largest jump — 606% or 42,000 unfilled orders — followed by CP with 394% and 11,000 unfilled orders.

“Given railways exist in specific, immovable locations, if railroads that control a large portion of grain movements experience service disruptions, a correspondingly large portion of shippers and product delivery will be impacted since those routes cannot be easily shifted,” Munch said.

“When grain shippers are unable to receive orders from railroads it disrupts agriculture markets throughout the broader supply chain.”

In some cases, flour and feed mills waiting on deliveries of grain are forced to temporarily cease operations, cutting off sales to customers until deliveries return.

“This means livestock operations that are reliant on the feed shipped from these mills may be forced to ration or stop feeding until deliveries return, or find alternative feed options, stunting the production cycle and putting the health and wellbeing of livestock at risk,” Munch added.

Farmers paying for storage in grain elevators that cannot move product may face added holding fees, contributing to even higher marketing expenses. In addition, Munch speculates that rail service disruptions will impact local basis for cash commodities that influence the price farmers receive for their crops.

Beyond creative solutions to immediately get rid of railway congestion issues, Munch predicts some producers may be forced to consider long-term investments in on-farm grain storage as a hedge against transportation disruptions.

Shipping rates out of control?

Average published per car grain rates were $5,195 in the first quarter of 2021, compared to $5,378 in the first quarter of 2022, marking a 4% increase. That equates to an average $1.37 and $1.41 per bushel respectively, according to Munch.

While railroads typically change published rates once or twice per year and are required by law to give a 20-day notice prior to changing rates, all bets are off when shippers who are looking to buy or sell a contract go directly to another shipper to receive or place bids.

“They are participating in the secondary rail market at that point,” Much said. “Sales that occur in this secondary market, may either represent a premium or a discount to the underlying original rate and are reported as a positive or negative value.”

When disruptions in rail service increase, Munch said shippers look to the secondary market as an alternative to get orders filled. High demand for cars in the current market is pushing premium rates far above the original underlying rate.

Comparing the weighted average premiums for the first quarters of 2018-21 to first quarter of 2022 shows nearly a 500% increase in secondary railcar grain auction bids, increasing from $102 to $602.

“The premium cost shippers are willing to pay in the secondary market helps illustrate the severe magnitude of demand for grain rail contracts so far in 2022,” Munch said.

Similarly, bids in the secondary market for shuttle service have escalated significantly — just in the past several weeks. USDA defines a shuttle train as having more than 75 cars that originate at a single origin and go to a single destination.

For the week ending March 24, bids for April delivery were over $2,500 higher than the prior three-year average for shuttle railcars, marking an 11-fold increase.

“Both secondary market metrics signify how service disruptions in existing contracts force shippers to enter the secondary market and attempt to obtain different contracts to get orders delivered, albeit at a super-inflated rate,” Munch said.

Rail car inventory questionable

Current rail car inventory threatens any quick rebound in service and will compound shipping delays. Munch said railroads that made COVID-related decisions to liquidate assets, such as railcars and locomotives, are now left with gaps in their ability to fill orders.

Making matters worse — a new round of COVID-related shutdowns across China has halted movement of around 10% of the global container-ship fleet and with it, a significant portion of containers.

Intermodal containers, or shipping containers, are used across multiple modes of transportation, including ocean and barge to railway or truck, have been affected.

“Containers held up oversees can limit order movement domestically and put added pressure on other car and container types used by agricultural buyers,” Munch said.

And, in true trickle-down fashion, Munch said current manufacturing disruptions and delays for new locomotives and containers are, ironically, restricting railroad capacity.

Source: Michigan Farm News