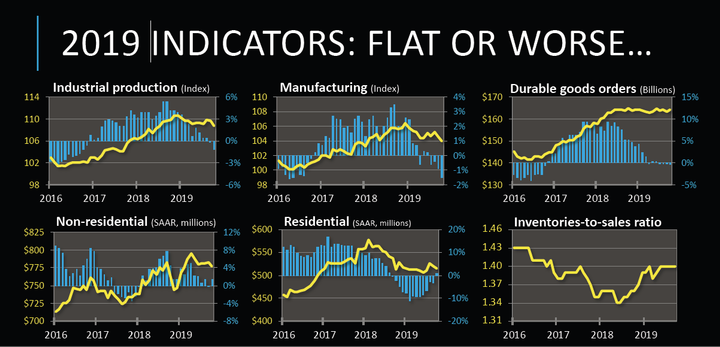

Economic indicators on the industrial side have been “meh” in 2019 at best.

Courtesy FTR

While it’s been a challenging year for the trucking industry in some ways, comparisons to the runaway market of 2017-2018 may make it seem worse than it is. In their monthly State of Freight webinar Dec. 12, the transportation intelligence analysts at FTR discussed the top trends affecting freight volumes and rates in trucking, rail and intermodal.

“Carriers aren’t doing as well financially this year because rates have fallen and cost increases such as driver compensation and insurance are things they cannot lower abritrarily or unilaterally,” said Avery Vise, vice president, trucking. It’s not that freight demand has fallen off that significantly, he said. “It might be true that carriers thought there would be more freight volume than there was, but that’s really a separate issue. When we look back at 2019, it was still a pretty robust market in terms of volume.”

Rates are more of a problem than volume, and that pain has been felt mostly in the spot market, not in contract rates, Vise explained. Overall, truckload rates are down about 6.5%, he said. “But the spot market and contract market experiences are vastly different.” Contract rates have fallen only about 1% this year, coming off sharp increases in 2017-2018. Vise expects them to remain fairly steady going forward.

The spot market is a different story.

“The big whipsaw has been with carriers that are much more dependent on the spot market, and in general that’s smaller carriers. The sharp drop in spot rates is probably a contributor in the surge in for-hire carriers going out of business,” he said, with the help of the aforementioned surge in insurance premiums.

For the last four quarters, he said, the number of carriers losing their operating authority has been well above the long-term trend.

“I have to stress that we look at this data as an indicator of financial stress, not a proxy of what’s happening with capacity,” Vise noted. Carriers might have lost their authority because they were owner-operators who decided to become company drivers, or may have sold their operations to another company. The numbers also don’t account for new operating authorities.

GDP, the industrial sector, and the consumer

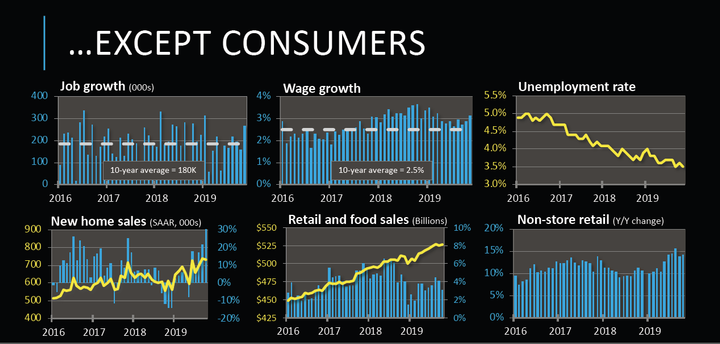

Looking at the economy as a whole, Vise explained that the industrial sector has had a lackluster year, but the consumer side of things is still strong – thanks to the growth in e-commerce.

The consumer is driving economic growth, especially e-commerce.

Courtesy FTR

He shared graphs showing industrial production, manufacturing, construction, and durable goods orders for 2019 at flat or worse. However, job growth, wage growth, new home sales, retail and food sales, and non-store retail (e-commerce) continued to show growth, while unemployment remains near historic lows.

Retail jobs are disappearing, he noted, while courier and parcel-delivery jobs are one of the fastest-growing employment sectors. “There is an ongoing change in distribution patterns and we have only just begun to understand what that’s going to mean,” said Vise.

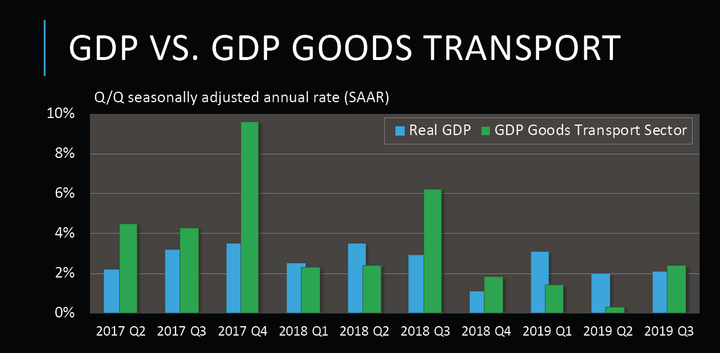

Vise also pointed out that a more accurate number to evaluate the health of the economy as it pertains to trucking is not the GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, but the GDP Goods Transport Sectors, which adjusts GDP to look at goods, not services, and includes imports as a positive contributor. (GDP counts imports as a negative factor because it’s not domestic.)

“The GDP Goods Transport Sector outpaced GDP for all of 2017 and ’18. This year, however, the first two quarters the opposite was true, with it rebounding somewhat in the third quarter to be about on par with GDP.” Trade issues have been distorting these numbers for more than a year, he said.

GDP Goods Transport is a version of Gross Domestic Product that zeroes in on the numbers that affect freight volumes.

Courtesy FTR

Intermodal growth disappoints

But while issues with trade wars and tariffs have been a problem, said Todd Tranausky, VP, rail and intermodal, the uncertainty caused by those problems is the real culprit.

“It’s hard to talk about 2019 without talking about trade,” Tranausky said. “It really is the marquee theme of the year, like capacity was 2018. It dominated the headlines. Trade took a lot of blame for weakness [in intermodal], especially on the volume side. But trade can’t be fully blamed for all of the weakness that we’ve seen. The bigger issue was the uncertainty it created,” he said, as people were more cautious in making investments and conservative in supply chain decisions.

“Trade and the uncertainty shifted volume around, but it wasn’t what caused the volume weakness; it was the uncertainty of people being able to plan that hurt intermodal volume.”

That and other challenges meant intermodal volume stayed very close to historical averages in 2019, not the growth driver it has been for the better part of a decade.

Looking to 2020

“Despite all the talk of failures and soft rates,” Vise said, “I think the word that describes 2019 best is steady.”

Looking ahead, Vise said, “the general outlook we have is for a very gradual firming [of rates] in the trucking industry. So we don’t expect any kind of big moves, nothing like we saw in 2017 and ‘18. We expect contract rates [next year will be] similar to this year; we came into the year with rates higher year over year and they have softened since; in 2020 we will start off lower and get a little stronger – but the net will be about the same.”

The impact of regulatory changes is expected to be minimal in the near term.

IMO 2020, a regulation that will see ocean-going ships using a higher grade of fuel that could cut into diesel supplies, is not as much of a concern as it was earlier in the year, Tranausky said. “We think right now any sort of supply disruption will be relatively short lived,” he said. If you’re a trucker, you’ll see in the price at the pump, but we don’t expect any impact to be long term. It could be 5, 10, 15, 20 cents a gallon, but that will only last a month or two or a quarter at most.”

The final implementation of the electronic logging device (ELD) mandate as of Dec. 17 is not expected to have a major effect on freight, Vise said. “We don’t see it as a huge problem; nothing I think that is market moving.”

The new drug and alcohol clearinghouse that starts up in January won’t have an immediate impact, but it may have a longer-term impact on truck driver availability, Vise said. “Our current estimate is that we would be looking at around 14,000 drivers a year taken out of the market, and that is a fairly aggressive assumption. However, assumption we did not make is what might transpire if the issue is not only drivers trying to hide [positive drug tests], but also carriers also trying to hide from other carriers. There’s a risk of that being a bigger impact.”

The bigger issue, he said, are regulations working its way through the federal government that will allow hair testing to be used to meet federal drug-testing regulations and eventually for that data to be included in the drug and alcohol clearinghouse. Because hair testing is more likely to catch longer-term “lifestyle” drug users, who can’t just wait a couple weeks for drugs to get flushed out of their system before taking a pre-employment drug test, that could have a larger effect on the commercial driver pool, he said.

The proposed changes to the hours of service rules are unlikely to have any effect before at least 2021, Vise said, “but it would significantly undo a lot of the restrictions that were put into place in 2004 on the driver’s workday and the 14-hour clock. That’s going to have a significant loosening on those restrictions, increasing potential productivity, and I think it is potentially market-moving as well in terms of rate pressures or lack thereof.” In other words, that increased flexibility trucking has been asking for could mean looser capacity and lower freight rates.