In 2019, greenhouse gas emissions from Christie’s global operations as an international auction house of fine art, design, and collectibles amounted to about 50,000 metric tons. Most of these

emissions were created from shipping items and people around the world, and from energy used in their galleries and offices, including employee commuting.

A year later, as the global pandemic took hold and shrank art transport and business travel needs at the auction house, its global emissions plunged 52%, according to a 2021 environmental report prepared for Christie’s with Avieco, a London-based sustainability consultant. What the Covid-19 crisis revealed is that Christie’s can run a successful business while “doing those things a lot less,” says

Tom Woolston,

Christie’s global head of operations.

Christie’s is among several arts organizations with ambitious goals to reduce their own emissions and to advance the adoption of climate-friendly practices throughout the art world, a sector that may not seem problematic, but spends a lot of time moving objects and people to openings, art fairs, and auctions. Several groups of arts professionals have banded together to change course, including Galleries Commit and Artists Commit in New York and Art + Climate Action in California.

One leading initiative is the Gallery Climate Coalition (GCC), a largely volunteer group of global members initially spearheaded by London gallerists and other United Kingdom arts professionals, including top officials at Frieze, the art fair organization, who came together just before the pandemic with shared concerns and a quest to learn what they could do about it within their own operations. In less than a year of videoconference meetings, the group began outreach through a website the members developed and created an open-source, art-business-specific carbon calculator. The GCC grew from a handful of members in March 2020 to more than 500 today.

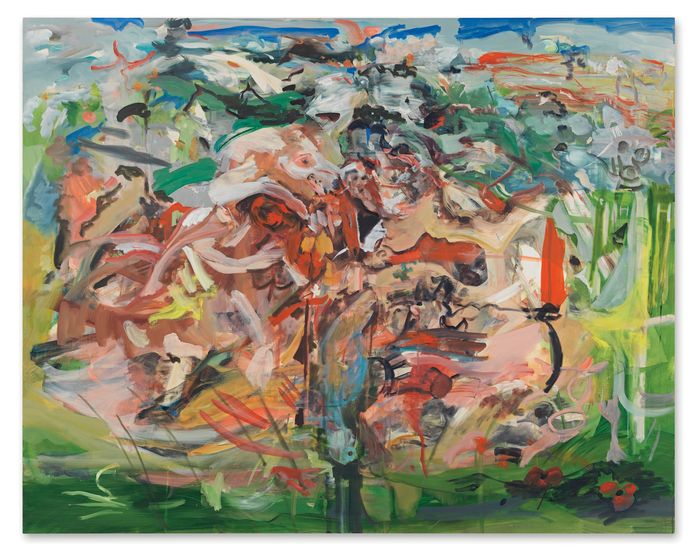

Cecily Brown’s There’ll be bluebirds, 2019, sold for £3.54 million ($4.8 million) to benefit ClientEarth.

Art by Cecily Brown. There’ll be bluebirds, 2019, oil on linen, 134.62 x 170.18 cm. 53 x 67 in. Cecily Brown. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo by Genevieve Hanson

“We all felt, as so many people did, that there’s a pandemic going on, but there are deeper problems that we’re not addressing,” says Thomas

Dane,

owner of a London-based gallery.

As a group, the initial members of the coalition realized their goal should be to cut their own carbon emissions by 50% by 2030—in line with the international Paris Agreement on climate change. For their efforts to matter, they also knew they had to get the word out to others in the art world on why cutting emissions matters, and how to do it, and they had to support outside organizations advocating for regulatory and policy change to combat climate change.

For most commercial galleries and auction houses the biggest source of emissions is shipping and travel—which in both cases is usually done by air—typically followed by energy used in their buildings. At

Thomas Dane

Gallery, with locations in London and Naples, Italy, art transport accounted for 45% of its 2018-19 emissions, while at Christie’s it was about 39% in 2019.

“We can change that,” Dane says. “I don’t need to fly across the world to go to a commercial opening of an artist that I represent. It’s too silly.”

Dane and others in the coalition, which Christie’s has joined, have started on a path to cut emissions by first documenting how much carbon they emit annually, and then figuring out how to reduce it.

This March, Christie’s, for instance, declared its intention to be net zero by 2030, and published what is expected to be an annual environmental report detailing its emissions. “The challenge is to ensure that we don’t go back to pre-2019 behavior patterns,” Woolston says.

One way it’s doing so is by purchasing renewable energy through green tariffs for its London offices. It’s also working to procure renewables for the rest of its global locations.

Heath Lowndes, managing director of the Gallery Climate Coalition, and Aoife Fannin, GCC’s administrative assistant, at Frieze Art Fair in London.

Ben Westoby

Art transport is more complicated to solve. The most energy efficient—and cost efficient—way to move art from London to New York, for example, is to send it by sea, not air. An analysis done for artist Gary

Hume

in 2018 by climate consultant

Danny Chivers

found the emission costs incurred from moving works from Hume’s London studio to Matthew Marks Gallery in New York resulted in 96% fewer carbon emissions when shipped by sea instead of air.

Of course, shipping by sea takes much longer—roughly three weeks versus a day—“and there is a perceived higher level of risk that filters into collectors’ confidence and insurers’ as well,” says Heath

Lowndes,

managing director of the coalition.

To address that perceived risk, the coalition has been meeting with a group of insurers who, after examining GCC research and having conversations with shippers, are gaining confidence in sea freight, Lowndes says. Insurers are now working on guidelines such as requesting galleries to ask sea shippers to transport artwork within a lower-deck container and to test the container to make sure no light is seeping through—a sign it’s airtight, he says.

The art sector also has to overcome what Lowndes calls social hurdles, such as the desire by collectors to have artworks delivered immediately after purchase. “It’s very rare an object has to be there so urgently,” he says.

Getting that message across is part of what the art sector has to do in its effort to be “a lobby for change,” Dane says.

One high-profile way of raising awareness is through a series of auctions at Christie’s over the next year of works donated by artists, including

Cecily Brown,

Antony Gormley,

and

Rashid Johnson,

and their galleries, including Thomas Dane,

Hauser

&

Wirth,

and White Cube. The funds raised will support the global nonprofit ClientEarth’s work in leveraging the legal system to stop climate change.

It’s the kind of collaboration that’s needed, Woolston says, because “we’re not alone—we inhabit an interconnected ecosystem in an international market.”

This article appeared in the December 2021 issue of Penta magazine.