Migrants from Cuba, Haiti and other countries are taking to the sea in sharply rising numbers as they flee political and economic turmoil at home and try to reach the South Florida coast.

The voyages are often aboard vessels that are rickety, overloaded and devoid of safety equipment, according to U.S. officials. Conditions at sea can rapidly and unexpectedly deteriorate. Human-smuggling groups that operate such crossings frequently fail to take basic precautions, officials said.

The recent capsizing of a Bahamian boat off the coast of Florida that left nearly 40 people presumed dead was an especially disastrous end to the sort of journey that officials said often goes awry.

“Maritime smuggling poses a lot of significant and serious risks that land smuggling doesn’t have,” said

Anthony Salisbury,

special agent in charge of Homeland Security Investigations’ Miami office, which is investigating the recent capsizing as a potential case of human smuggling.

Cuban migrants on a sinking vessel spotted earlier this month about 40 miles off Key Largo, Fla.

Photo:

U.S. Coast Guard/Associated Press

Coast Guard interdictions of migrants from Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, who account for most of the migration toward the southeastern coast, totaled 2,383 people between Oct. 1 and Jan. 31, according to agency figures. That is on pace to more than double the tally in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, 2021, and more than quadruple the count in the previous fiscal year. Interdictions have increased as well off the coast of California—driven by Mexican and Central American migrants—and off the coast of Puerto Rico, propelled by Dominican and Haitian migrants, agency officials said.

Coast Guard data show that total interdictions across all of the agency’s districts are on track to match those in 2016, a high point in the past decade, just before the end of the U.S.’s “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy, which gave Cuban émigrés special treatment. Still, the maritime figures are small compared with those for attempted land crossings at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Various factors are fueling the rise, which, though significant, pales in comparison to maritime migration waves in the 1990s, said

Kathleen Newland,

co-founder of the Migration Policy Institute, a research organization. Conditions have worsened in countries such as Haiti, where violent gangs have filled a political vacuum, and Cuba, where the economy is crippled and the government has increasingly cracked down on dissent. Legal paths to enter the U.S. remain limited, she said.

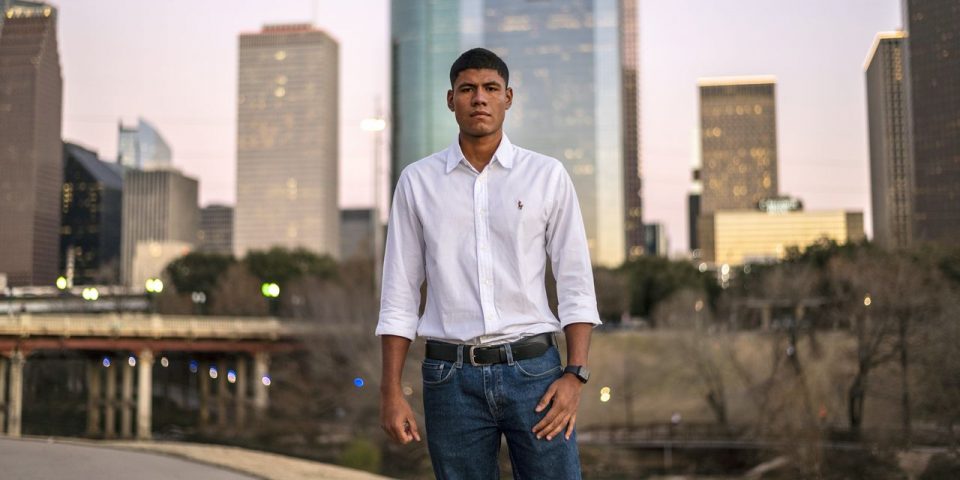

Juan Esteban Montoya,

the 22-year-old sole survivor of the recently capsized boat, said at a Spanish-language news conference on Jan. 31, where he was joined by his attorney,

Naimeh Salem,

that he decided to leave Colombia because of a lack of security and economic opportunity. Researching on the internet, he read comments saying it was safer to make the journey to the U.S. by sea rather than land. He traveled to the Bahamas, where he boarded a boat along with migrants from countries including Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Jamaica.

Juan Esteban Montoya showing a photo of himself with his sister, Maria Camila Montoya.

Photo:

Sergio Flores for The Wall Street Journal

Hours after departing on Jan. 22, the boat’s motors gave out, Mr. Montoya said. The sea turned rough, triggering 12-foot waves that tossed the vessel and eventually capsized it. His 18-year-old sister was swept away, along with most of the others, none of whom had life jackets, he said.

The roughly 15 passengers who managed to cling to the boat gradually succumbed over the following two days, losing their grip or giving up, until he was the sole survivor, Mr. Montoya said. He thought he was going to die, he said, but on Jan. 25, a commercial-boat operator rescued him.

Smugglers “tell you that in three, four hours you’ll be in Miami…that you are going with few people, that it is safe, that there are life jackets,” Mr. Montoya said. “It is all a lie.”

Many smuggling operations are criminal organizations that transport not only people, but drugs, weapons and other cargo, said Mr. Salisbury of Homeland Security Investigations. The current rate they charge a migrant seeking to get to the U.S. from the Bahamas is $3,000 to $6,000, he said.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

What steps should the Biden administration take to address migration pressures? Join the conversation below.

Migration has increased along key routes in recent months, said Lt. Cmdr.

Jason Neiman,

public-affairs officer for the Coast Guard’s Seventh District in Miami. They include departures from the Bahamas, which often involve organized smuggling ventures; from Cuba, which include many makeshift vessels; and from Haiti, which typically entail overloaded sail freighters.

The California coast is experiencing an increase in migration as well, from the Mexican coast, according to Coast Guard officials. Smuggling groups using pleasure boats or fishing vessels known as pangas are venturing farther out to sea and trying to land farther up the coast to evade authorities, they said. Last May a boat with 33 people shipwrecked off the coast of San Diego, resulting in three deaths and numerous hospitalizations, according to officials.

Maritime migration in the Pacific presents additional challenges, including colder water and potentially rougher surf, said Lt. Cmdr.

Scott Carr,

public-affairs officer for the Coast Guard’s Pacific Area. “It is fraught with risk,” he said.

In Puerto Rico, apprehensions of migrants by U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Ramey Sector in Aguadilla have reached 816 since Oct. 1, a more than eightfold increase over the same period a year earlier, said

Scott Garrett,

acting chief patrol agent. While most making the journey across the passage between the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico are Haitians and Dominicans, other groups including Venezuelans are appearing as well, he said. Some have been dropped off without provisions on uninhabited islands off the coast.

Smuggling organizations “have zero concern for life and safety,” Mr. Garrett said. “All they’re looking for is the dollar that they’ll put in their pockets.”

Juan Esteban Montoya, with his mother, Marcia Caicedo, in Houston this week.

Photo:

Sergio Flores for The Wall Street Journal

Write to Arian Campo-Flores at [email protected]

Copyright ©2022 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8