The Environmental Mapping and Analysis Program, or EnMAP, is capable of measuring things that would otherwise be invisible, from the degree of pollution in a river flowing through a forest to the nutrient supply within a plant.

“There have already been great moments, and I can’t wait to see the data … there are so many possible implications,” EnMAP Mission Manager Sebastian Fischer told CNN a week after EnMAP was successfully launched on April 1.

EnMAP’s data will help scientists track and examine environmental changes in realtime — whether they are natural or manmade — and potentially help to develop the next generation of longterm climate forecast models, Anke Schickling, who oversees the EnMAP mission’s Exploitation and Science Program, told CNN.

“We will receive even more reliable information about man-made changes and damage to our ecosystems in the future,” said the state of Brandenburg’s Minister of Research, Manja Schüle. “These are the best prerequisites for developing innovative measures to adapt to climate change.”

“Everyone is really excited to just get the data and understand if their algorithms and the ideas of what they want to do with the data can really hold up to what they’ve been preparing for over the last couple of years,” Schickling said.

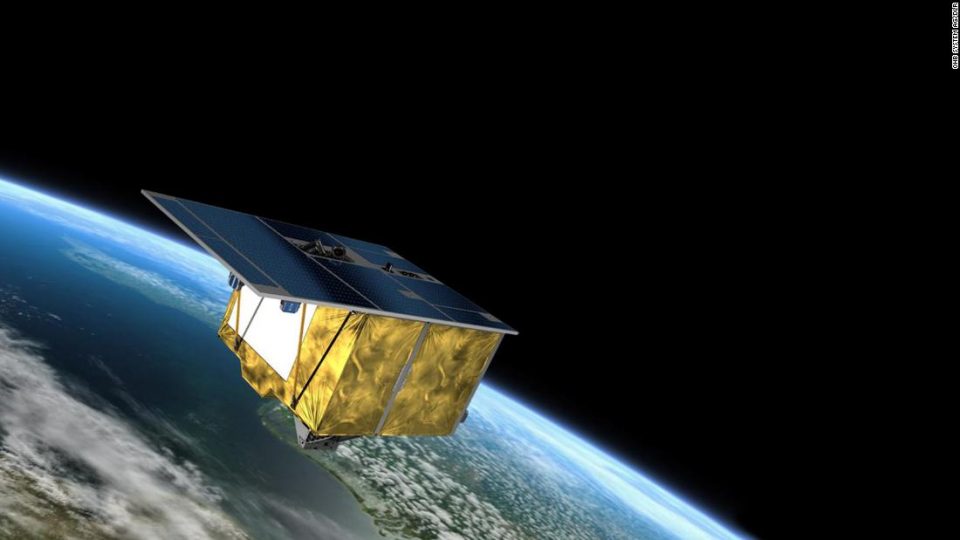

Understanding how light interacts with different materials — like plants, water or soil — makes it easier for researchers identify them and define their characteristics from a distance. The satellite’s technology uses the nearly 250 different colors to more accurately and specifically determine the characteristics of the land or water it observes.

The spectrometers on the satellite first capture a photo of a section of the Earth below it. Rather than assigning the entire photo one color to categorize it, the satellite dissects each pixel of the photo and assigns each one its most appropriate color on the spectrum. This allows for historical precision.

“Each element the satellite observes is like a fingerprint — one of a kind,” Schickling said.

All materials on the planet’s surface reflect sunlight in a unique way. The relationship between how something reflects light and the color assigned to the material is called a spectral signature. These spectral signatures are unique identifiers for EnMAP.

“Without Earth observation from space, it would be very difficult to quantify the global extent of the climate crisis and its consequences,” says the Federal Government Commissioner for Aerospace Anna Christmann. “Germany is making an important contribution to European space technology and to an intact planet.”

The satellite is designed to withstand the harsh conditions of space for at least five years, but scientists are hopeful EnMAP lasts longer for optimal data collection. And even though the EnMAP satellite is the first of its kind, there are already successor missions underway.