Our Truth, Tā Mātou Pono is a Stuff project investigating the history of racism. Part one has focused on Stuff and its newspapers, and how we have portrayed Māori. Business reporter Anuja Nadkarni analysed how we have reported on the Māori economy.

ANALYSIS: Of the more than 300 business stories I have reported for Stuff this year, only four were about Māori – the list includes a story about cultural appropriation, and another related to Matariki.

Looking at my own bias while working on this project highlighted the fact our business news still fails to acknowledge successful Māori trade and enterprise and entrepreneurship.

More than 160 years ago, in the decades following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, our earliest mastheads were established. They were a sign of the times.

This analysis is part of the national Our Truth, Tā Mātou Pono project, which found Stuff and its newspapers have been racist. Collectively, our team of reporters discovered we’ve contributed to social stigma, marginalisation and negative stereotypes against Māori.

Stuff apologised to Māori for its monocultural lens that hasn’t served our journalism principles well for all of Aotearoa. This includes how we’ve represented Māori businesses and the Māori economy.

Many of Stuff’s newspapers were created by Pākehā settlers, for Pākehā settlers as mass migration from the 1860s brought more Europeans to New Zealand.

But much of the early trade set up and dominated by Māori was either ignored or misreported in our papers. A look through our early newspapers shows our reporting rendered Māori invisible.

SIDELINING MĀORI TRADE AND ENTERPRISE

Overtime, we’ve been better at reporting on general Māori issues, but business coverage is still mainly focused on Pākehā.

In our reporting, Māori were mainly spoken about or on behalf of, by Pākehā.

Historians and academics have also found despite displaying business acumen historically and currently, Māori businesses have been represented in the media as incompetent or unfairly privileged due to a lack of context.

As recently as this year, our business reporting on Māori has made it to the Stuff homepage only when the topics were controversial.

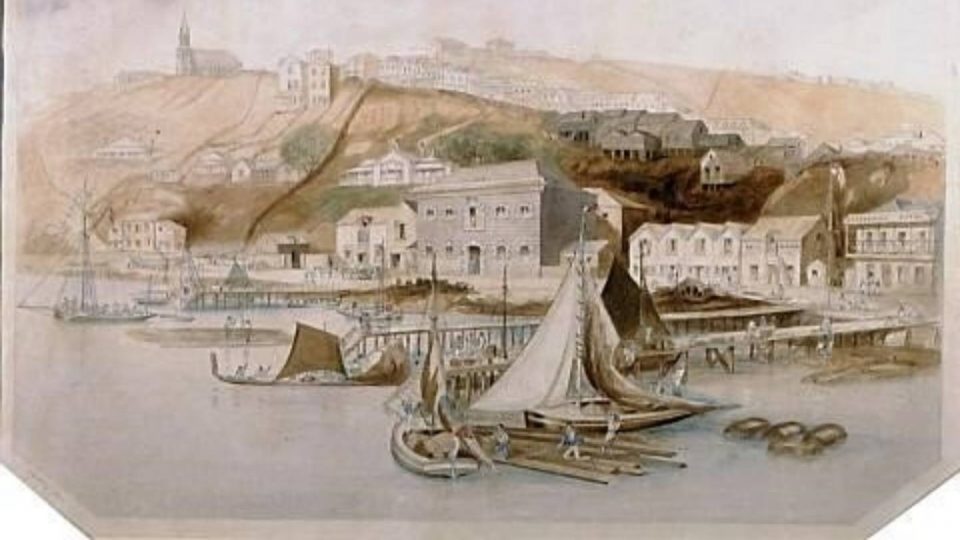

SUPPLIED

The bustling markets of Auckland in the 1850s when Māori traded with Pākehā settlers.

Rightly, we covered at least a dozen stories this year on Pākehā brands and businesses appropriating Māori culture, while small enterprise issues or Māori company profiles were not approached with the same enthusiasm.

Only a handful of stories about the impact of Covid-19 on Māori companies were reported on in the plethora of Covid-19 related businesses stories.

Our reporting, or lack thereof, has contributed to the perpetuation of Māori being “other” than the norm in the mainstream media.

RICKY WILSON/stuff

University of Auckland professor on Māori economy and entrepreneurship Kiri Dell says business is not at the forefront of the average Māori interest in the mainstream media.

University of Auckland professor on Māori economy and entrepreneurship Kiri Dell said the coverage of racism, unconscious bias and people being wronged was “sexier” than business news.

“Failing health and education systems and uplifting of babies is what people gravitate towards. When we start to put business talk into the mix, it just doesn’t seem as urgent as some of these other pressing social issues. Business is not really at the forefront when it comes to Māori issues,” Dell said.

THE EARLY MĀORI ECONOMY IGNORED

One of the earliest attempts by our papers to report on the early Māori economy appeared in the Auckland Star in 1928, the paper said it was the “white man who brought trade to New Zealand”.

“The Māori knew nothing of trade promotion, not even barter. He had a very high intellect, but he knew nothing of commerce he had no knowledge of the luxury of driving a bargain, but after the coming of the Pākehā he quickly learned,” the article said

Numerous studies by researchers and academics have shown Māori were traders and had an established economy well before European settlers arrived.

SCREENSHOT

Business story published in the Auckland Star in 1928 “Our Early Trading Address to Business Men”.

A 1943 story in the Auckland Star titled “Māori People” showed our lack of cultural understanding.

“The inevitable difficulties encountered by the Māoris in adjusting themselves to the conditions of European life and economy are but little understood; but offences which often are direct consequences of maladjustment receive prominence.”

This excerpt illustrated coverage of the Māori economy in the 19th and 20th centuries.

It’s an early example of a perpetuating narrative Māori had an unfair advantage or were given handouts from the Crown following the Treaty of Waitangi.

“Nor will these problems be solved by lavish grants of public money. Money will be needed, but a greater need is to afford the Māori people better opportunities of education and training to help themselves,” the Auckland Star reported.

Send your tips, story ideas and comments to [email protected]

Dell said the traditional Māori economy was rooted in intangible value, trade was relational not monetary, it was an “economy of mana”.

“The value of relationships was essential because if you didn’t have good relationships with other hapū, you couldn’t trade and access special resources others had in their area,” Dell said.

This difference between the two economies, the collectivist nature of the Māori economy and the individualistic nature of the Western capitalist economy, influenced our reporting of business issues for decades.

Māori trade with Pākehā settlers up until the early years of the New Zealand Wars, was thriving as iwi quickly adapted to Western capitalist trade.

LAWRENCE SMITH/Stuff

Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei deputy chairman Ngarimu Blair says for Māori to be thriving, competing and in some cases dominating markets was unacceptable to the colonial mind.

Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei deputy chairman Ngarimu Blair recalled how his ancestors’ entrepreneurial prowess laid the foundations that turned Auckland into an economic hub.

“We wanted to attract Europeans to Auckland from Kororāreka and the South Island, so we could trade items including new medicines, building materials and new weapons to secure our future.”

After the signing of the Treaty, the tribe thought their land was being leased out, said Blair.

To the Crown, it was an outright sale. 3000 hectares of land was transferred to Governor William Hobson, to make Auckland the economic capital of Aotearoa in 1841.

Much of this history and the betrayal the iwi felt was not reported until the 20th century.

SUPPLIED

A log book from 1854-58 the number of waka in the Auckland harbour, which tribes and then the list of all the produce they sold.

In the early years, a bustling market dominated by Māori sold all manner of fish and produce to Pākehā settlers at Auckland’s first port at the junction of Pania Rise, Junction St and Beach Road, Blair said.

“There were Pākehā traders too, but Māori could outperform and undercut all the settlers because [Pākehā], based on individualism, had to pay wages, which forced up their production cost.

“But our businesses were based around communalism. To be part of the tribe and the community and the village you had to pull your weight. So our costs of production were a lot lower which meant we could run settlers out of business.”

Blair said news reporting ignored the successful trade and enterprise of Māori entrepreneurs to protect the interests of settlers.

“In the psyche of the colonial empire Britain, it’s probably unacceptable that there be savages from the South Seas not only surviving but thriving, competing and in some cases dominating markets,” Blair said.

HOW WE UNDERMINED MĀORI TRADE

In our earlier papers Māori culture and customs were ridiculed and undermined.

For instance, a story published in the Marlborough Express in 1907 said the “modern hui” held in a marae, was a “perfect medium for the dissemination of disease”.

SCREENSHOT

Marlborough Express, August 8, 1907 story about the modern hui.

“The business – if there is any to be done – is conducted by a sort of informal debate, which is often carried on far into the night … A crowd of men, women and children are packed together, more closely than the passengers on an emigrant ship,” the article said.

The narrative of Māori being incompetent has been perpetuated in our coverage for many years.

Economist and researcher Matt Roskruge said the media has been quick to write about the failures of Māori.

A lack of relationship and understanding between the mainstream media and Māori business structures has meant journalists have felt more confident reporting on issues that have been through the courts, Roskruge said.

Dominico Zapata/Stuff

Māori economist Matt Roskruge says the media is quick to write about the failures by Māori businesses.

Iwi also faced greater scrutiny because of the perception they were getting “handouts” from Crown settlements, he said.

“Farmers rely heavily on infrastructure subsidisation yet Māori funding structures are seen as handouts.

The Waitangi Tribunal has done a lot of good but has also perpetuated some opinions around any subsidisation, which is a shame.”

The Evening Post published an article in 1946 claiming Māori had no desire to enter business.

The article quoted then Minister of Rehabilitation Jerry Skinner, who said Sir Apirana Ngata was unfairly favouring the rights of Māori servicemen.

“In business loans assistance has been given to one Māori in 60 and one Pākehā in 37. Considering that far fewer Māoris have any desire to enter business, those figures are an adequate reply, but on the other hand one Māori in 95 has received a loan to buy tools of trade as against one Pākehā in 158.”

SCREENSHOT

Frank Greenall 1948 published in the Sunday Star Times in February 1992, Shows Treaty Settlements Minister Doug Graham shaking hands with Tipene O’Regan and speaking to him and other Maori. Refers to the settlement of Maori claims for compensation for loss of fishery rights.

A story by Stuff in 2012 wrote about Taranaki iwi, Ngāti Tama, losing close to $20 million after a series of high-risk financial ventures failed.

The iwi’s kaumatua Wiremu Matuku said he expected a “heavy burden of shame and accusation” following our coverage.

“One of Taranaki’s largest private investment projects has gone horribly wrong … Ngāti Tama, has shed all of a $14.5m Treaty of Waitangi payout it received in 2003. Shocked iwi members learned of the financial disaster at a hui,” Stuff reported at the time.

Matuku said in the article: “Unfortunately for Ngāti Tama’s estimated 5000 members, what they read in your newspaper will be the first time they will hear of this terrible news.

“Our tribe is devastated, not only by the news, but also by the realisation that once it becomes public Ngāti Tama will be battered by speculation over why various investments went so bad. We are going to have to carry a heavy burden of shame and accusation.”

That story concluded by writing about what the iwi could have done with their Waitangi Tribunal “payout” if it had been conservatively invested instead.

‘MAKING LOAVES OF BREAD AND CRUMBS’

Following the New Zealand Wars of the late 19th century, the mass immigration from Europe, and the introduction of new diseases, the Māori population was significantly reduced.

By the turn of the 20th century, settlers no longer needed Māori and were sufficiently trading among themselves.

Blair said for four generations Māori were shut out of the economy.

LAWRENCE SMITH/Stuff

Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei deputy chair Ngarimu Blair says tribes have turned scraps from Crown settlements into billion dollar assets.

“On the back of the Waitangi Tribunal Act 1975, it would take until 1991 that we would have a small transfer of resources and assets back, beginning with $3m for 3ha of land for commercial activities.

“The tribes have taken crumbs off the Crown table and made loaves of bread,” Blair said.

In the years following its $18m plus interest settlement, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei has turned its asset base into a $1.3b organisation today.

THE MODERN MĀORI ECONOMY

In 2007, fed up with the portrayal of Māori in the public discourse, prominent Māori business leader Paul Morgan decided, along with economic researche company BERL, to measure the Māori economy.

“What really drove me to do this was the negative coverage of Māori in the media as not contributing to the economy or being on the dole,” Morgan said.

The study showed the Māori economy contributed $2.5b to the national GDP in 2003, today it’s expected to be worth more than $50b.

Morgan said Māori enterprise is rooted in New Zealand’s future and cultural values.

SUPPLIED

Paul Morgan chairman of Wakatū Incorporation worked with BERL to calculate the worth of the Māori after feeling frustrated about how Māori were represented in the media.

“Our businesses are intergenerational for our tangata whenua. We’re not going anywhere, our money is going back into helping our communities,” Morgan said.

Our coverage at Stuff and its newspapers over the last 160 years has continued the settler narrative.

We’ve improved our representation over time, but a lack of historical context has led to Māori issues being reported on from a distance.

However uncomfortable it might be for us, in the media, to face the history of our reporting, we must strive to do better.

To engage with the intent of listening, interview without assumption and report with historical context.

After all, reporting with fairness, accuracy and balance and being representative of all people in New Zealand is upholding the fundamentals of journalism.

Our Truth, Tā Mātou Pono is a Stuff project investigating the history of racism. In 2021, part two of the series will focus on Aotearoa and how our racist past has made us who we are today.