Physicians, nurses, and other allied professionals have and will continue to be on the front lines of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis. In the first phase of the crisis, these professionals confirmed fears that our system was unprepared to address an emergent public health threat. Both urban and rural areas have reported a desperate lack of medical products in regions where resources such as masks, gloves, ventilators, other personal protective equipment (PPE), and prescription drugs might be needed most. We are now moving toward a second phase of the crisis, as COVID-19 transitions to a chronic public health threat. This change poses its own challenges to medical product procurement including affordability given the dire finances of some local hospitals.

Uncertainty in the supply of medical products has real consequences. Supply problems hasten the unintended spread of the disease but also heighten health care disparities along lines of geography, race, and class. Ensuring the supply of adequate medical products is critical to ameliorating disparities in the spread of COVID-19 and associated outcomes.

In facing the first phase of the COVID-19 crisis, the Trump administration made clear that local hospitals, individual cities, and the states should be self-sufficient in sourcing products, forcing them to compete against each other as well as the federal government and other countries for the same products. Therefore, the federal response to COVID-19 builds on our current medical product procurement system, where each medical provider sources its own products overseen by federal and some state rules. The administration’s response is grounded in a political philosophy of federalism—where it is presumed local community control will produce higher-quality and more efficient outcomes compared to top-down federal control. While this presumption makes much sense in normal times, the administration’s response is a departure from how the federal government has addressed historic crises that have significantly threatened our health and our wealth.

Here we review the current US medical product purchasing and distribution model and discuss the current federal response to challenges raised by the COVID-19 crisis. We then suggest several improvements to that response.

The Current Medical Product Purchasing And Distribution Model

Reports of shortages, price gouging, and the hoarding of certain medical products needed to address COVID-19 have emerged as concerns among hospitals and state governors. These challenges highlight an underappreciated fact: Americans depend on medical supplies and prescription drugs that are largely made by international companies located in Southeast Asia and Europe. With each US hospital sourcing these products alone, hospital procurement officers are running into a bewildering array of middlemen, international procurement rules, import quotas, and exorbitant freight charges. Supply quality is also a concern, as hospitals encounter unvetted brokers and counterfeit goods. Moreover, as the crisis transitions into a chronic concern, the finances of hospitals, particularly those that serve the safety net, are now at risk. For some hospitals and communities, the purchasing of potentially needed supplies at exorbitant “crisis” prices can become an existential threat.

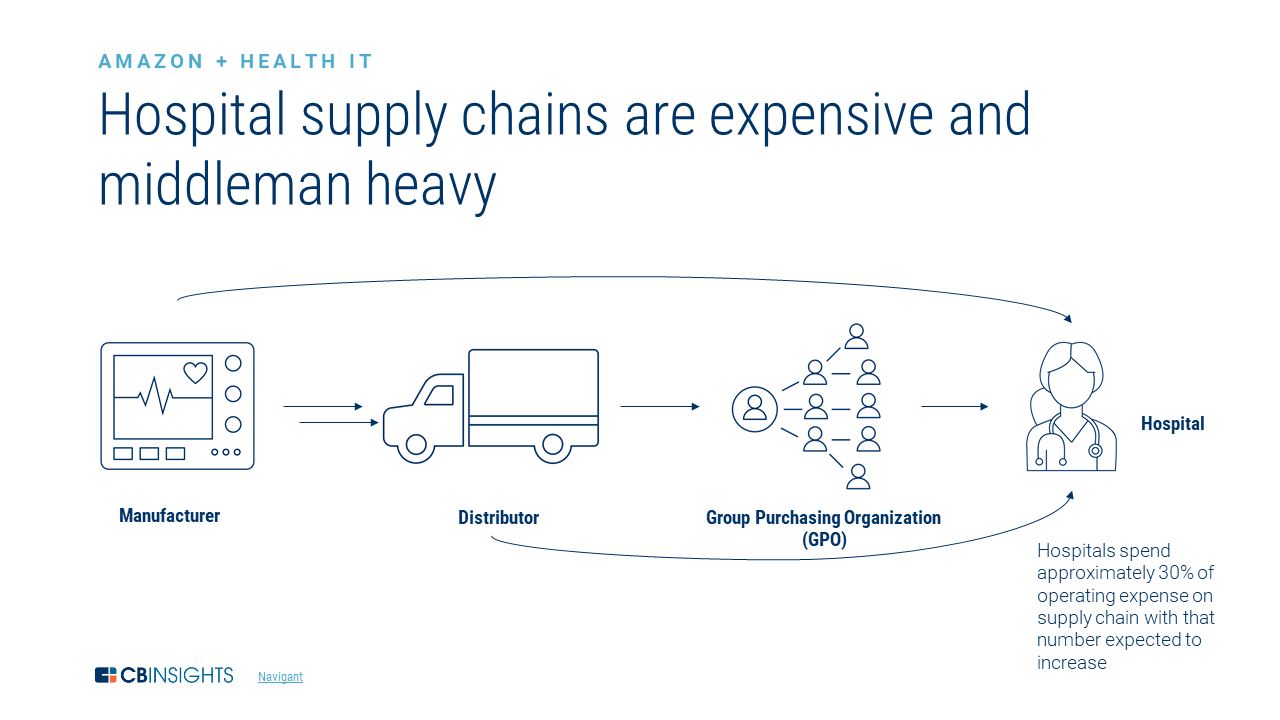

Hospitals require many medical products including PPE and prescription drugs on a regular basis. Most hospitals maintain a procurement officer or department to manage their inventory and order when needed. They do this themselves or through their parent institution. While hospitals can source products themselves through wholesalers, most contract with group purchasing organizations (GPOs), such as Premier Inc. (exhibit 1). GPOs aggregate demand across many hospitals, buy supplies in bulk, and in many cases obtain better prices for products than individual hospitals can by themselves. In exchange, hospitals pay membership fees to GPOs. GPO memberships are rarely exclusive arrangements, and it is common for a hospital to be a member of multiple GPOs.

Exhibit: Medical product supply chain

Source: CBInsights.

GPO contracts feature characteristics that make them challenging partners for hospitals when there is a surge in demand or shortage in supply. First, larger purchasers of medical products, including regional/national hospitals, tend to receive preference over smaller hospitals in traditional GPO arrangements. This can lead to disparities in access across hospitals, even in the same city or country.

Third, most GPO contracts do not contain “failure to supply” arrangements that would hold them accountable for failing to supply products that they are unable to procure and that hospitals require. This leaves hospitals to source needed products on their own.

Fourth, there are no product price guarantees in a typical GPO contract. This means that manufacturers of these products can and do charge prices above the contracted amount and what may seem reasonable when there is a surge in demand or in the prices of base products and ingredients. While US states have price gouging laws, cross-border federal laws fall under the umbrella of trade and tariffs and don’t prohibit price gouging.

Fifth, GPO contracts do not guarantee the quality of products that they procure for hospitals. For some products, minimum quality standards set by regulators serve as a backstop. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates the quality of most prescription drugs and maintains a database of approved PPE manufacturers as a resource to hospitals. However, many products procured by GPOs are not regulated by federal agencies, which incentivizes suppliers to maintain very low-quality standards or even cheat. There is also no public information about the quality of products sold by manufacturers. GPOs and wholesalers have no legal or contractual obligation to provide this information to their members.

The lack of purchasing power and information regarding quality leaves hospitals that procure medical products on their own at a distinct disadvantage in facing COVID-19. Since the manufacture and distribution of many of these products cannot be scaled up to meet the demand of every local medical provider in the US and worldwide, the transformation of the COVID-19 crisis into a chronic threat only heightens these challenges.

Current Federal Policies to Address Supply Chain Challenges

The Trump administration and Congress have pursued several policies to mitigate the clinical and economic consequences of these challenges. We group these efforts into several categories by purpose and, further, by federal agency responsibility.

Adequate Production Of Needed Medical Products

President Donald Trump signed an executive order invoking the Defense Product Act of 1950 in March 2020. The act allows the federal government to compel domestic companies to produce needed medical supplies. As of this writing, it appears that the federal government has been reluctant to use this provision to meet COVID-19 medical product shortages. One notable exception is its use to compel manufacturing of swabs for COVID-19 diagnostic testing, announced in mid-April.

The FDA has activated numerous pathways to reduce regulatory hurdles for the approval of novel COVID-19 tests and drugs. These actions are important to reduce barriers to entry among willing manufacturers of these products. On the other hand, the FDA has also suspended inspections of many existing products that the agency regulates, likely contributing to delays in increasing the supply of these products and putting the quality of these products over time at risk.

Alleviating Hospitals’ Immediate Financing Needs To Fund The Purchase Of Needed Medical Products

The $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act contains an additional $100 billion for hospitals, which averages out to about $108,000 per bed. All hospitals that received Medicare fee-for-service reimbursements in 2019 are eligible for the funds, distributed in proportion to overall revenue they generated last year. Eligible hospitals are allowed to use the funds to purchase medical products if not reimbursed by other payers. As of this writing, approximately $30 billion of the fund has been released to hospitals. Meanwhile, the hospital’s lobbying group, the American Hospital Association, has been urging the Trump administration to release the remaining funds as soon as possible.

Oversight

While the secretary of Health and Human Services has broad discretion over how CARES Act funds are distributed to hospitals, there is limited oversight over the allocation or use of those funds. There are emerging concerns that the funds may not reach the hospitals that need them most, including those serving rural and less well insured communities.

In late March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched a voluntary nationwide system for tracking the availability of certain medical products such as ventilators to care for patients with COVID-19. The system captures reporting by hospitals but not clinics and outpatient medical providers, and tracks the availability of certain supplies, such as ventilators, while excluding others including diagnostic tests and prescription drugs.

Further Improvements To The Current Federal Response Are Needed

While such efforts by the federal government support the financing and procurement of needed medical products to address the adequacy of medical products to meet the COVID-19 crisis in the short run, they do not form a cohesive strategy to address COVID-19 as a chronic public health threat.

One possible improvement over existing efforts would be for federal policy makers to further define the criteria for hospitals and other medical providers to receive CARES Act funds. Additionally, understanding where the appropriated funds have already gone and how they have helped providers meet the needs of patients and their community will help inform whether and how to deploy additional funds when available.

A second improvement would be for federal policy makers to consider adding additional data collection to existing CDC oversight efforts. Additional data on a broader set of medical product availability could be voluntarily sourced from health care stakeholders including hospitals, clinics, GPOs, and wholesalers. These data could be augmented by existing FDA data related to drug supply and potential disruptions, and new reporting policies for problems in the supply and quality of needed medical products. Claims and admissions data, along with fine-grained, de-identified electronic health record data, might also be added.

Increased reporting would allow for rapid assessment of medical product needs and help match those needs with available supplies. It might also help discriminate between products that are directly reimbursable by payers and those that are not to improve targeted financing efforts. Broader oversight efforts would have the additional benefit of lessening the incentives for unethical sellers to price gouge or cheat on quality of production. They might also help to ensure equity of access to needed products, especially when paired with local and regional procurement efforts such as the recently announced seven state consortium.

Broader data collection might have an additional benefit of allowing the federal Strategic National Stockpile to allocate their resources at the right time and at the right place. Designed to rapidly supply medical providers during public health emergencies, the Stockpile held up to about $7 billion in supplies, including 13 million N95 masks, before the response to the first phase of the pandemic quickly diminished this supply. Keeping the Stockpile current is critical for ensuring quality of care throughout the chronic phase of this pandemic.

Third, policy makers might want to consider pursuing policies that reinforce both the demand and supply of these medical products. For example, similar to banking requirements under Dodd-Frank after the 2008 financial crisis, policy makers might wish to consider requiring hospitals and local public health departments to hold minimum supply stocks of certain supplies that meet existing safety and quality standards and to periodically report their availability to the Stockpile. Minimum supplies would act to smooth out demand for products held at the local and federal levels.

Lastly, policy makers may wish to pursue policies that would minimize the United States’ global supply risk. These would include rules and preferences mitigating reliance on a few countries that currently generate the bulk of the basic ingredients and finished medical products. India’s banning of various essential medical product exports to the US earlier in the spring (now lifted) emphasizes the need to diversify sourcing for both quality of care and national security reasons. As we were writing this piece, the president signed the “Buy American” executive order. The order outlines an initiative to review all federal purchases with preference to buy US-made goods. It also includes additional directives to federal agencies to recommend ways to strengthen the implementation of “Buy American” laws including domestic procurement preference policies and programs.

Here, additional policies might be considered to encourage production of raw materials for crucial medical supplies and raw ingredients for pharmaceuticals and other needed medical products that would be available in the US in the event of international disruptions. Policies might include favorable economic incentives and environmental regulations for US companies to ensure that material is locally sourced and that manufacturing facilities can be adapted for rapid production. Federal price gouging rules might also be considered.

The benefits of these and other efforts need to be carefully considered, as domestic manufacturing will take time to execute in practice. There are also costs to consider in pursuing these policies. Diversification of medical supply production to higher-income countries will increase costs of goods, inflicting some additional burden on our health care system.