Procurement within the NHS is managed by the NHS Supply Chain, with little input from clinicians. This article discusses the opportunities for and benefits of increased nurse involvement, highlighted during the coronavirus pandemic

Abstract

The nursing profession is inconsistently involved in the NHS procurement process, despite the proven benefits of their greater clinical involvement. This article explores what procurement is, how it is undertaken in the NHS, and how nurses can support and improve this process. It examines reports into NHS Supply Chain as well as case studies, to discuss the impact of clinical involvement in procurement, particularly during the coronavirus pandemic, and concludes that patient outcomes can be improved by greater collaboration between clinicians and procurement teams.

Citation: Chapman N, Hudson K (2021) Making the case for nurses’ increased involvement in NHS procurement. Nursing Times [online]; 117: 2, 25-27.

Authors: Dr Naomi Chapman is clinical director, Towers 1 and 3; Karen Hudson is clinical programme lead, Tower 1; both at NHS Supply Chain.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

Introduction

Patient pathways are diverse, with care delivered in various settings, including homes, health centres, care homes and acute care services. Each setting uses a wide spectrum of products, from uniforms to complex scanners, ventilators and monitoring equipment (which is considered a product) – and these must be procured.

Although clinicians’ jobs would not be possible without these products, little thought is given to where they come from or how they have been selected – understandably, we only have such thoughts when the shelves are bare or a product to which we are accustomed changes. However, some NHS organisations and groups of nurses, recognising that it is critical to have the right product, are seeking ways to integrate product and procurement knowledge into their clinical roles. Some nurses have moved into specific procurement roles but, in many cases, more needs to be done to fully harness the nursing community’s knowledge and insight to inform purchasing decisions.

This article investigates how important nurses’ involvement and influence can be in the NHS supply chain, explores how NHS procurement works in England – including the role of NHS Supply Chain (NHSSC) – and recommends greater clinical involvement to enable a paradigm shift in product quality and value.

NHS procurement in England

In its simplest terms, procurement can be considered shopping on an organisational scale. Behind that apparent simplicity, however, run rules, legal requirements and a national model of how disparate parts of the NHS can work together. Everything used in a clinical setting – from pillows and couch roll to surgical equipment, patient food and crockery – must have a precise description (a specification), against which it is procured, manufactured, stored, delivered and paid for.

Most NHS trusts and organisations have procurement teams, whose role is to ensure the trust or organisation has the correct amount of each product it uses. These teams are overseen by NHSSC, which manages the sourcing, delivery and supply of healthcare products, services and food for NHS trusts and healthcare organisations across England. It manages more than 4.5 million orders per year, across 94,000 order points and 15,000 locations, consolidating orders from over 800 suppliers. Ultimately, this saves trusts time and money by avoiding duplication and overlapping contracts.

NHSSC was remodelled in May 2018 to put the clinical voice and view of quality at the centre of the procurement process. Before this, procurement was often considered a separate part of each organisation; each trust bought items, with no transparency or comparison of cost. There were also no economies of scale, as individual trusts could not make savings based on the volume of items procured by the NHS countrywide.

The system resulted in a huge variety of similar products being used, with no overview of stock holding or turnover. These findings were reflected in Carter’s (2016) report into efficiency and productivity in acute trusts in the NHS. Its core finding was that there was unwarranted variation in procurement across the NHS; as a result, it highlighted the need to transform fragmented procurement processes. Its findings were the focus of the NHSSC redesign.

NHSSC was created to help the NHS procure clinically assured, high-quality products through a range of specialist buying functions to take advantage of the buying power of the NHS and negotiate the best deals. Its current target is to deliver savings of £2.4bn back into NHS frontline services by the end of the financial year 2022-23.

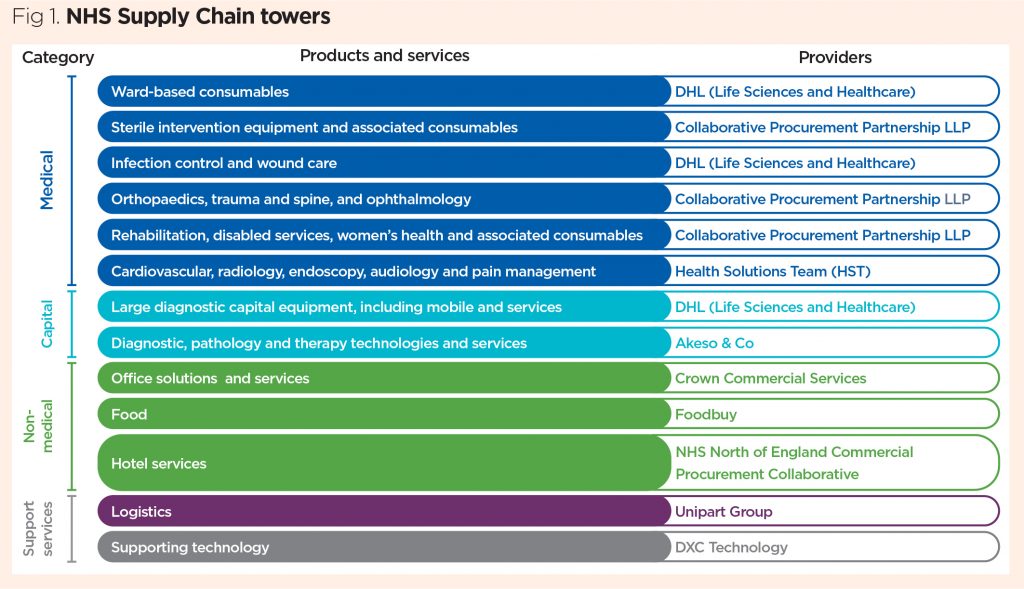

The current model comprises 11 specialist buying functions, known as category towers. The towers are divided into clinical areas, types of medical equipment, and non-medical products such as food and office solutions (Fig 1). They undertake the buying aspect of procurement and are managed by Supply Chain Coordination Ltd (SCCL).

Other services manage the storage and distribution of products before they reach the trust: the logistics and inventory teams are responsible for NHSSC’s delivery and storage of items. Trusts contribute towards the funding of NHSSC and, although they can each buy directly from suppliers or pursue a different procurement route, they are encouraged to draw on the strength of the towers.

Clinical involvement

Given the range of products used across the NHS on a daily basis, it is clear there is a need for clinical involvement as part of this process. At present, however, the extent of such involvement varies greatly from trust to trust and function to function.

In many trusts, some nurses are aware of the procurement teams and involved in clinical engagement groups, where they help identify or introduce changes in product choice or manufacturer. This informal relationship is quick to set up; and does not need a specialist role to be created; however, such roles can be helpful in identifying product options and suppliers.

A step on from this is the role of clinical procurement specialist, which exists in some trusts; the role sits in the trust’s procurement team and is filled by a clinician. It has proven to be of great benefit – for example, when a specialist has worked with fellow clinicians to identify a product that best meets the trust’s needs, enabling them to buy at larger scale, thereby, unlocking savings and, perhaps, safety benefits. Until recently, Professor Mandie Sunderland occupied this role in Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (NUH) and showcased the success it can have: due to the significant input of nurses, the trust’s procurement team has supported safety and value changes in products such as catheter packs.

Despite, traditionally, not being involved in procurement, research has shown there is a clear appetite among nurses to change this (Carter, 2016). In recent years, nurses at all levels have become increasingly aware of the impact of procurement on quality, cost and safety, feeling that they can – and should – be more involved. As part of the Small Changes, Big Differences campaign, run by the Royal College of Nursing, NHSSC and the Clinical Procurement Specialist Network, 87% of nurses said patient safety could be improved if nurses had greater involvement in the procurement process. However, there has been no clear route or system in place to allow a wider range of clinicians to contribute to the procurement process, or to do so more frequently.

As primary users of many products in the NHS, nurses are uniquely placed to judge whether they are fit for purpose. As clinicians, they can quickly identify products that do not function as required or have unnecessary additional attributes. They can directly inform the procurement team of the exact specifications required for each product procured nationally and also have detailed knowledge of:

- How products work and fit together;

- Problems and solutions that arise with products in practice;

- How these solutions can be built into procurement itself.

In 2016, Professor Sunderland, formerly chief nurse at NUH, was asked by the then-Department of Health to set up a national pilot exploring how clinicians could contribute to the understanding of product quality in the NHS. As part of this pilot, the NHS clinical evaluation team was set up; it independently reviewed the healthcare consumables used daily by the NHS to identify the products that enabled staff to provide the highest standard of patient care and deliver the best outcomes for the NHS.

The pilot concluded when the new NHSSC model went live, with new clinical teams created in the appropriate towers, which are now responsible for the commissioning and procurement of clinical products. A clinical and product assurance directorate has also been created in SCCL, which has an assurance role for the products provided via NHSSC.

How clinical teams ensure quality

Clinical involvement in the procurement process aims to improve quality and patient outcomes. A full procurement exercise can take many months, as it involves:

- Working with product users to develop a detailed product specification;

- Putting the specification out to tender;

- Evaluating the submissions.

During the first part of this process, the tower’s clinical team conducts broad and detailed stakeholder engagement – either face-to-face or via digital platforms – to understand the clinical pathway and future needs for each product group. This end-user engagement model is used in many towers and aligns with the recommendations in the report by the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review (2020) on product-user engagement. Each tower uses the findings of its stakeholder engagement to form the central part of a strategy document; it submits this to SCCL’s clinical and product assurance directorate, which approves the quality approach for each strategy.

Typically, the quality approach details:

- The stakeholders engaged with, for example, patient groups or trust types;

- How the approach will align clinically with any changes in practice to ensure it is futureproof;

- Product specifications, including size, material, standards, adherence, design;

- How the products will be tested against those specifications.

Each tower uses this detailed, thorough approach to cover every aspect of items procured, ensuring a consistent level of quality, efficiency, cost-saving and patient safety.

The nursing influence in action

Each tower has a different approach appropriate to its product range, but all are guided by the same principles and focused on engaging with the correct stakeholders to inform the specification of the product being procured. An example of procurement where clinical engagement is crucial is the need to ensure a simple product – a single-use pressure infuser – works in various ways.

The theatre team must be consulted to ensure the product pressurises 3,000ml bags of irrigation fluid to act as a distension medium, and to ensure the inflation pump allows for quick inflation while removing blood or tissue from the operating field during surgery. However, these same products are also used in critical care for a longer period to pressurise 500ml fluid containers to maintain an end-of-line pressure. The same product will be used by teams with very different needs and, as such, differing clinical views. It would not be possible to ensure the product is fit for purpose across a range of clinical areas without the insight of nurses – as the largest professional clinical group in the NHS, they have experience across health and social care settings.

The coronavirus pandemic

As the country continues to manage the coronavirus pandemic, sectors of business and society have begun to ask themselves how they have coped so far and how they can build greater resilience for the future. Procurement in the NHS is not exempt from this; the pandemic should be seen as an opportunity to take stock of the processes and systems in place, and accelerate improvements already begun.

As clinical knowledge and treatment of Covid-19 have rapidly developed, so too have the requirements of the products needed. For example, there was initially a focus on patients on ventilators, which developed into separate pathways for ventilation, oxygen, and oxygen-plus care; this required nurses in procurement to look ahead and ensure access to the specific equipment needed for those pathways. Without this nursing insight, it would have been a huge challenge to ensure the appropriate products were in place on time.

The events of 2020 have changed health professions universally, including those in procurement. The relationship between clinicians and procurement staff was strengthened during the first wave of the pandemic, as clinical teams navigated huge change and disruption. These challenges meant it was necessary for procurement teams to work alongside clinicians to ensure an effective response to evolving clinical needs. This teamworking in fields such as airways, respiratory and non-invasive ventilation meant it was possible to provide appropriate high-quality products at a time of incredibly high global demand.

The demand for these products was unexpected, urgent and challenging but the collaboration between the towers and NHS clinical and procurement teams resulted in increased mutual respect in organisations and ensured patients received the care they needed. It also meant the NHS was better equipped to deal with the second wave and any further recurrences of the virus.

Conclusion

The nursing profession is starting to be empowered to lead on clinical influence on product design, including human factors – in which a product’s use and user is considered, and value-based procurement. This will enable nurses to shape the procurement of products that are intuitive, fit for purpose and high quality, ensuring delivery of the best possible patient care.

Key points

- NHS Supply Chain carries out procurement, with limited and inconsistent clinical involvement

- Nurses are uniquely placed to advise on procurement due to their wide-ranging role

- Clinical involvement in procurement has shown financial savings and improved patient outcomes

- Joint working has been necessary during the coronavirus pandemic to ensure an effective response to evolving clinical needs

- The development of joint working systems is an opportunity to increase long-term clinical involvement in procurement

Carter P (2016) Operational Productivity and Performance in English NHS Acute Hospitals: Unwarranted Variations. UK Government.

Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review (2020) First Do No Harm. UK Government.