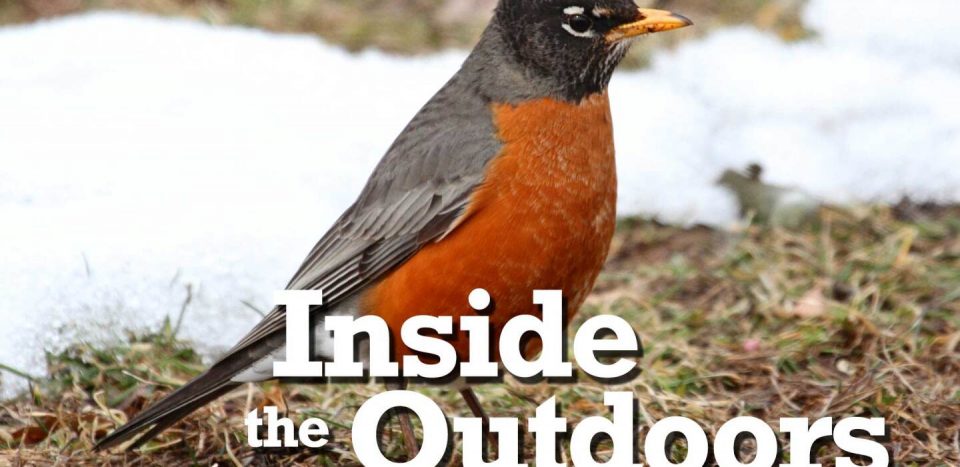

Late in the afternoon on Saturday, less than 24 hours before the official arrival of spring, I heard the familiar “cheer up, cheer up, cheerily” notes of my first robin of the new season. I had not heard this call since last November, when the last holdouts were leaving for more temperate places to spend the winter.

Some bird voices are unmistakable, and the robin’s is one. It may not be fully appreciated because of the robin’s abundance and familiarity. But when it hasn’t been heard for months, and is linked to the end of winter, it seems all the more musical.

I’m not a phenologist, one of those people who records the timing of Nature’s events so they can be compared from year to year. So I can’t say with any precision how this robin’s arrival compares with the spring of 2021. More easily remembered are the climatic conditions of a year ago, and last winter’s meager snow cover. This winter was vastly different. Despite the recent spell of above-average temperatures, there is still a blanket of snow almost everywhere. The ground is still frozen, so the prospect of a robin finding its favorite meal—earthworms—is remote. Yet here this robin was, perched on a snowbank, belting out a song to announce its return.

I am reminded of a television commercial advertising a service to help you unravel your own ancestry. Its purpose is to fill in the gaps in your knowledge of who you are descended from, and—with many of us having immigrants from Europe or elsewhere somewhere in our backgrounds—just where in the world we come from. “I want my children to know they come from people who were brave,” says the on-camera spokesperson in this commercial. “They took risks, big risks,” she says, as a film clip shows a sailing vessel on a forbidding expanse of ocean.

Migratory birds take risks, too. Big risks. Not the least of these—aside from the collisions, predation and other threats that accompany long distance travel to wintering grounds—is the timing of their return here. Nature has programmed into them an irresistible urge to aggressively pursue their life’s most important priority, which is to secure a territory, find a mate and raise the next generation of their kind.

One might think that such an early arrival would be unnecessary, given the number of months of pleasant weather before autumn. But raising nestling songbirds to adulthood is full of hazards, from nest robbing red squirrels, blue jays and crows, to prowling cats and even some hawk species. Sometimes an entire nest is lost. Even when a brood is successfully hatched, mortality is high; about 80 percent for robins. For this reason, robins commonly raise more than one brood in a season to compensate for their high mortality.

Photo illustration, Shutterstock, Inc.

Thus, the premium on getting an early start. But survival of “veteran” adult birds is not assured at this time of year, especially in the northern regions of the state. Most of the landscape is still frozen. Insect abundance is weeks away. Forage options are limited, consisting of seeds and withered fruits that might remain on shrubs and trees from last autumn, or that can be gleaned from patches of ground that are free of snow. Not the choice and abundance that would be theirs in April, or May.

Then there is the very real possibility of a major late March blizzard. This has been common enough during the state high school basketball tournament that “tournament blizzard” has become part of Minnesota’s weather lexicon. Not to mention the risk of an encore appearance of lengthy sub-freezing temperatures. This, too, can take a toll on early returning migrants, like my robin who announced its arrival on the day before spring officially arrived.

Another risk-taking migratory bird is one dear to the hearts of many bird hunters. It’s the American woodcock, an odd, mysterious creature that strikes one as part upland bird—like the ruffed grouse, and part shorebird—like the snipe or the sandpiper. The woodcock’s home address is that intersection where aspen and birch forest meets wetland, the interface often thickly grown to alders. The woodcock has a long, thin, pencil-like bill that is tailor-made for probing soft ground for earthworms, though it will eat other invertebrates—insects—if the opportunity presents itself.

But in late March and early April when the woodcock arrives here there are few earthworms or other invertebrates to be had. A magnet for early-arriving woodcock is the wet, soft soil along streams and in places where small feeder brooks empty into wetlands. These—especially if they are south-facing—are the first places to thaw. They’re the first places where earthworms will be available to woodcock.

Photo illustration, Shutterstock, Inc.

In a pinch, woodcock are said to supplement their preferred earthworm and insect foods with seeds, sedges and other foods from the vegetarian side of the menu. This is the time of year when they are most likely to have to temporarily make these dietary concessions. Some of those who hunt woodcock might actually prefer that woodcock make this a year-round habit. Their summer and fall diet is chiefly earthworms, and the flavor of their dark flesh is thought by some to resemble liver!

Like the early-arriving robin, wintry spring weather has been known to victimize woodcock. A heavy fall of snow, and temperatures that plummet significantly below freezing, are not what the woodcock’s anatomy was designed for. Brief spells can be survived, but not lengthy ones. The most complete records of weather-killed woodcock come from their wintering grounds in the South. This is understandable, given their concentration in limited habitats there. But when woodcock have come north in spring, and are dispersed into habitats mostly remote from humans, observing weather-killed birds is a much longer chance. But if extended sub-freezing temperatures and a blanket of snow can kill them in the South, the same would be true here, especially after enduring the rigors of their northward migration.

These are not the only migratory creatures that come north hard on the heels of retreating winter, and in doing so risk a counter-attack of harsh weather capable of killing them. But they have evolved as successful, thriving species with this risk-taking habit built-in. So who are we to question Nature’s blueprint for their survival?