SINGAPORE — Emerging Asian markets are on course for the worst half year in over a decade, as investors retreat from large tech companies in the region, while recession fears build up.

Heavy rate hikes by central banks, the repercussions of China’s severe lockdown and global supply chain disruptions are behind the investors’ deteriorating sentiment. Analysts say regional markets may struggle to attract capital inflows this year, with the pace of central bank interest hikes creating the main near-term uncertainty.

A multitude of risks from the COVID-19 pandemic fallout and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could also weigh down on recovery efforts more generally.

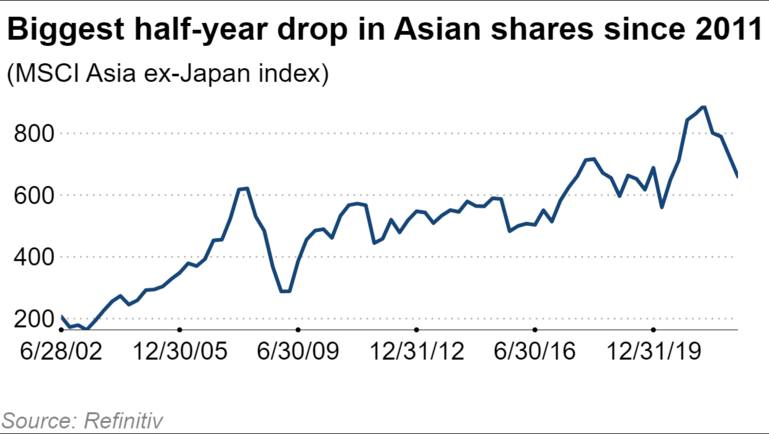

As of June 22, the MSCI AC Asia ex-Japan Index — a gauge of the region’s most-tracked stocks outside Japan — had dropped around 18% this year compared to the previous six months. This was the the biggest half-year decline since late 2011. The index mainly covers emerging markets with China and Taiwan accounting for about half, and South Korea and India for around 15% each.

“The twin shocks of high inflation and sharp policy tightening at major developed economies are resulting in a cost of living crisis and slowing activity,” said Aninda Mitra, head of Asia macro and investment strategy at BNY Mellon Investment Management in Singapore.

In March, the U.S. Federal Reserve raised its policy rate for the first time in about three years. As inflation continued to soar, the Fed decided to raise the interest rate by 0.5 percentage points in May, the largest hike in 22 years, and by 75 basis points in mid-June — the biggest rate hike since 1994.

“These matter for Asia, as most emerging market countries are highly open to trade and susceptible to shifts in global demand,” said Mitra. “As such, the downshift in growth and earnings expectations has pulled most Asian equity indices lower.”

Europe has also been affected. The European Central Bank announced early this month that it will end quantitative easing from July and raise interest rates for the first time in 11 years. The Bank of England has been raising interest rates for five consecutive meetings since December 2021.

“Central banks collectively seem to be frontloading their hiking cycles more and more, given continued upside surprises in inflation,” said Peggy Mak, head of research at SAC Capital, a corporate advisory specialist.

“The markets are pricing in concerns that these attempts to bring down inflation could lead to demand destruction that drags the economies into recession,” she said.

The last time the MSCI AC Asia ex-Japan Index saw such a big drop was in the second half of 2011 when it went down 19% in the wake of Japan’s catastrophic earthquake and tsunami. The disaster compromised a significant proportion of the world’s supply chains, most notably in the automotive industry.

In 2011, a series of sovereign debt crises intensified as Europe struggled to avert a Greek default and ease fiscal pressures in Italy and France. Despite restructuring efforts by authorities, investors grew concerned the Eurozone could enter another recession, impacting its trading partners in emerging economies, particularly China.

Emerging Asian markets fell broadly at that time, with Shanghai’s SSE Composite Index dropping the most by 20%. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index, the Taiwan Capitalization Weighted Stock Index and India’s benchmark BSE Sensex index all fell by around 18%.

This year, however, the drop in emerging Asian markets stems from rising interest rates and a slowing global economy. High-growth tech stocks have been unable to retain their high valuations.

The MSCI AC Asia ex-Japan Index is highly exposed to the technology sector, which accounts for about 25% of its total value, and this is the primary reason for the downturn this year. That has been particularly acute in South Korean and Taiwanese stocks with a semiconductor downcycle caused by concerns over inventories building up.

Nikkei Asia reported this month that Samsung is temporarily halting new procurement orders and asking suppliers to delay or reduce shipments of components and parts until the end of July because of high inventories.

Reflecting weakening consumer demand and rising global inflation, this move by the world’s largest smartphone and TV maker has affected suppliers of parts, such as panels and chips.

Similarly in Taiwan, where the index tracks companies like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and MediaTek, some corporations are flagging in the face of weak demand and high inventories. Mak at SAC Capital said this points to “slower build-up of inventory in the second half of the year, and possibly destocking in the first quarter of 2023.”

Moreover, heavily weighted players include companies like TSMC, Tencent Holdings and Samsung Electronics. The top three weighted companies were the leading losers, with each dropping around 20% of their value already this year.

Large Chinese companies have been among the most notable underperformers in the region. Lockdowns in major cities affected consumers of e-commerce giants like Alibaba, JD.com and Meituan.

“COVID resurgence and the subsequent widespread roll-out of lockdown measures have impacted the economic activity and momentum of the nation in a big way,” noted Andy Budden, Investment Director at Capital Group.

Meanwhile, Southeast Asian markets — which are relatively small compared to emerging East Asian markets — were some of the gainers during this uncertain period. “Equity markets of net commodity exporters — and less open Asian economies — have done relatively well,” said Mitra at BNY Mellon Investment Management.

Commodity-intensive countries like Indonesia and Malaysia have been relative bright spots in the region. They have benefited from reopening after the COVID-19 pandemic, more subdued inflation and the generally positive outlook for commodities. MSCI’s Indonesia index is up 4.6% so far this year. Though Malaysia was down 8.6%, the drop was small in comparison to its regional peers.

Even though it is an open-economy and not a net commodity exporter, Thailand also fared well as the market reopened from pandemic restrictions, and the weakened Thai Baht improved competitive positioning and profitability for Thai companies. There is also the likelihood of a modest tourism recovery this year, although the industry remains far from generating the 20% of gross domestic product it managed in 2019.

“The reopening of economies bodes well for commodity-based and tourism-reliant countries, particularly economies in Asia with sizable domestic populations,” said Sailaja Devireddy, head of fund marketing services at Acuity Knowledge Partners, an Indian financial research firm.

Even so, some analysts believe the greatest danger to this rosier outlook is whether Southeast Asian central banks can properly calibrate normalization of monetary policy. If central banks raise rates too fast, there is a risk of staunching economic growth, while raising rates too slowly could stimulate capital outflows and currency depreciation.

Nearly all Asia-Pacific countries have initiated monetary policy normalization, except for Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia, according to Moody’s Analytics. Each is likely to commence policy tightening during the third quarter of this year, if not in late June, following the U.S. Federal Reserve’s aggressive 75 basis point hike this month.

“Emerging markets might not be able to raise rates at the same pace, as this could hurt export competitiveness and weaken domestic corporates ability to borrow,” said Mak at SAC Capital. “But failing to keep pace might weaken the fiscal balance sheet and cause risk of sell-down of emerging market currencies.”

Additional reporting by Dylan Loh in Singapore