The press release issued by the U.S. Department of Commerce on Jan. 25 declares: “Commerce Semiconductor Data Confirms Urgent Need for Congress to Pass U.S. Innovation and Competition Act.”

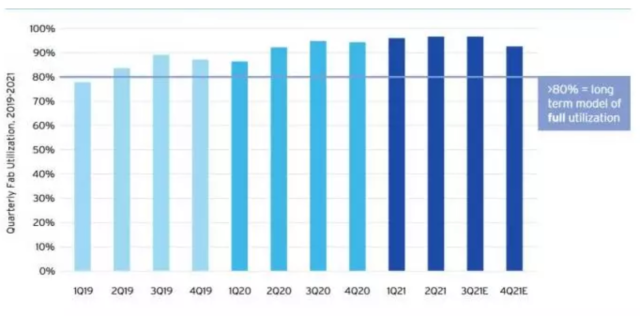

Not quite. Mostly, the government data confirms ongoing technology supply chain disruptions, semiconductors being the leading indicator. The industry survey found that fabs are operating full-blast as pandemic-driven demand for chips has risen 17 percent since 2019.

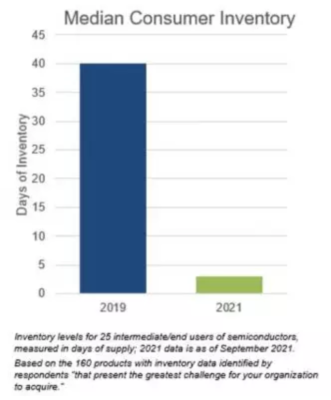

The supply-demand imbalance is also reflected in manufacturers’ inventories: The semiconductor supply chain report also reveals that median inventory among U.S. automakers and consumer electronics manufacturers has shrunk to less than a five-day supply from 40 days in 2019.

“The main bottleneck identified is the need for additional fab capacity,” the survey concludes. “In addition, companies identified material and assembly, test and packaging capacity as bottlenecks.”

That’s hard data, underscoring the direct economic impact of supply chain disruptions. But the findings do not on their own confirm, as Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo asserted, the need for Congress to immediately approve $52 billion to accelerate domestic semiconductor production.

Cast as a statement of fact, Raimondo’s interpretation of the supply chain data is typical of the industry cheerleading in which commerce secretaries often engage. It’s their job.

The reality is the final outlines of U.S. legislation to revive domestic chip manufacturing will be determined amid inevitable horse-trading during an upcoming House-Senate conference. Those tense negotiations will reconcile fundamental differences between the pro-industry Senate bill and House legislation that emphasizes semiconductor R&D and workforce training while addressing key challenges like sustainable energy production and climate change.

It’s likely the release of the Commerce Department data was timed to coincide with Intel’s Ohio fab announcement on Jan. 21 and last week’s introduction of chip legislation in the House.

Raimondo correctly described the semiconductor supply chain as “fragile.” But reaching for the conclusion that a fragile supply chain requires swift passage of the chip legislation that includes $52 billion to fund “surge” chip production strains credulity.

Momentum toward a major infusion of federal funding to revive U.S. semiconductor manufacturing seems inevitable. Massive private sector investments announced by Intel, Samsung and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. appear to have primed the pumps. All come with the expectation of federal subsidies.

Still, notes industry analyst Jim McGregor of Tirias Research, fab construction doesn’t always translate into immediate production.

Which raises the looming question of fab overcapacity if and when technology supply chains are untangled. Indeed, other analysts foresee a chip recession. “All the signs of a recession are there. The market is overheating, and the road ahead is stony,” declares Malcolm Penn, CEO of market tracker Future Horizons.

Sister website EE Times Europe also quotes Penn as predicting: “It is simply a question of when: the fourth quarter of this year or the first quarter of 2023.”

The pandemic has wrought wrenching economic change. Whether that includes breaking the chip industry’s traditional boom-bust cycle remains to be seen.

What is clear is the need to revive domestic manufacturing as a hedge against future supply chain disruptions. Congressional approval of CHIPS Act funding in some form appears likely. The challenge will be targeting those investments to advance the state of the art while rebuilding U.S. manufacturing prowess and, ultimately, boosting American economic competitiveness.