A surprising agreement

The agreement that led to starting work on the factory was signed three years earlier. On 23 September 2008, it stipulated a joint venture between Venezuela and Haier Electrical Corp Ltd. Haier, which has its headquarters in the city of Qingdao, is itself a joint venture – with both Chinese and German capital – but in practice it operates as one of the hundreds of Chinese state-owned companies and receives the preferential treatment reserved for them.

The partnership also aimed to foster technology transfer agreements and supply contracts to “achieve the country’s independence” in the medium term by producing and developing household appliances on Venezuelan soil.

But from the beginning of 2009, signs began to emerge that the letter of the contract might already be dead.

A report dated 11 February 2009, issued by the Ministry of Light Industries and Commerce and the Venezuelan Corporation of Intermediate Industries (Corpivensa), warned that Haier representatives had ‘expressed reservations in providing the information required to formulate the project’.

The document is one of a number of leaked Chávez government papers from 2009-12 that Armando.info has accessed and which, in alliance with the data team of the Latin American Centre for Investigative Journalism (Clip) and with additional reporting by Diálogo Chino, form the basis of the series El joropo del dragón (Venezuela’s dance with China). The series analyses various projects agreed between Caracas and Beijing.

The February report reveals the first doubts on Venezuela’s side that cast a shadow over the progress of a plan that, as with many others, started with so much optimism.

The agreement aimed to fill equipment shortfalls in the homes of low-income Venezuelans. The preliminary draft of the plan, presented to President Chávez, diagnosed that at the time of its drafting in 2009, 16.8% of the population did not have a refrigerator, 81.5% did not have an air conditioner and 45.7% did not have a washing machine, according to data from the Venezuelan National Statistics Institute (INE).

The goal was to bring the numbers of households without a refrigerator down to 4%, those without air conditioning to 19% and those without washing machines to 11% by 2021.

To achieve this in just eleven years, the Chávez government calculated that it would need to produce 488,555 refrigerators, 396,609 air conditioners and 489,555 washing machines at the new plant. If the rate were maintained, no Venezuelan household should be left without its white goods by 2025.

But just as the document was explicit and ambitious in its description of the binational project’s targets, it was vague in its reference to what was expected of the Chinese counterpart.

In 2009, the project barely sketched out what the function of the factory was, and tentatively acknowledged that it was not clear what the Chinese would provide: “It is important to note that, to date, Haier representatives have not provided information on the characteristics and physical properties of the raw materials and inputs to be used. Therefore, a further study will be required to determine new local suppliers,” the plan reads.

Among the supplies to be provided by the Chinese company should be refrigerants, low-power motors, sensors, thermostats, compressors and condensers, the report authors wrote. These would be some of the “parts and pieces mainly supplied by the Chinese company Haier, which is the shareholder of the joint venture and with whom the agreements for technology transfer, knowledge and supply of parts and pieces that Venezuela is currently unable to manufacture will be made”. However, it also notes that “the necessary information is not yet available to determine which parts will be supplied”.

Despite these doubts, on 18 February 2009, eight days after the preliminary report was submitted, Corpivensa proceeded to sign the agreement with Haier on behalf of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

Shipments kill-off factory

The document was remarkably ambiguous about the technology Haier would actually transfer to Venezuela. In the end, the Chinese company managed to sell more than US$750 million worth of finished household appliances to Hugo Chávez’s government.

In 2010, the supply of Haier’s ‘white line’ of goods helped Chávez and his political party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Psuv) to win parliamentary and regional elections of that year.

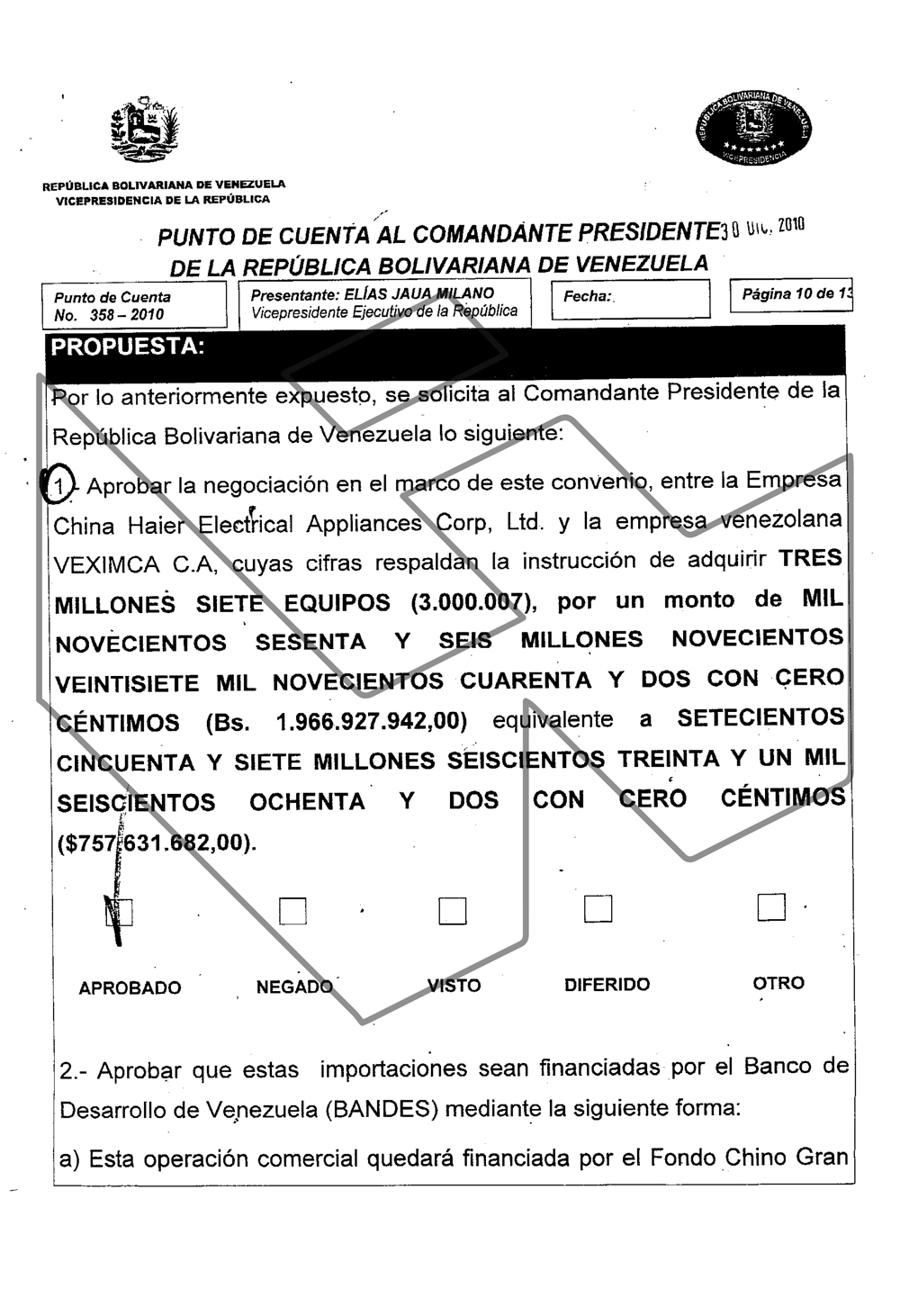

Then vice president Elías Jaua Milano proposed importing 19,672 containers with 3,000,007 household appliances, including gas heaters, televisions, DVD players, gas cookers, air conditioners, dryers, washing machines and refrigerators. In total, the purchase cost Venezuela $757,631,682, according to the contract seen by Armando.info that Giuseppe Yoffreda, president of the Venezuelan company Venezolana de Exportaciones e Importaciones C.A. (Veximca), signed with Haier Electrical Appliances Corp. Ltd. on 30 December 2010.

The amount was to be financed with resources from the Large Volume and Long Term Fund (FGVLP), a second body created in 2010, which together with the Venezuelan-Chinese Joint Fund, active since 2007, managed the China loans. FGVLP served to fund the ‘Mi Casa Bien Equipada’ (My Well-Stocked House) plan. As part of this social project, the small state-run markets, Mercal and Pdval, created by the Chávez government to sell food at low prices, would also sell the appliances. As part of the scheme, household appliances would be offered at prices of between 40% and 80% below those of private retailers.

In 2011, a washing machine made by brands such as LG, Samsung or Whirlpool ranged from 3,000 bolivars (US$697, according to the exchange rate of the time), while a Haier brand could be bought for half the price, just 1,472 bolivars ($342). A refrigerator of a competing brand cost around 5,000 bolivars ($1,162), while a similar one from the Chinese company cost 2,628 bolivars ($611). Credit, sometimes with no interest, enabled many purchases.

The Chávez government also offered credit through public banks to state employees to finance their purchases. Specialised state institutions, such as the People’s Bank or the Women’s Bank, offered loans to pensioners and poor families, respectively.