A rise in freight rates linked to the logjam in Chinese ports earlier in the year is adding to the issues for the frozen seafood sector, already under pressure as the spread of coronavirus globally causes havoc in economies.

However, when the global container capacity gets back in sync and with trade likely to be down in the COVID-19 pandemic, prices could come down rapidly, sources told Undercurrent News.

The rise in freight rates started with the African swine flu (ASF) crisis last year and prices firmed further amid the coronavirus crisis, multiple sources told Undercurrent.

“I would say the rates have gone up around 80% since Q2 last year to now, even with the surcharge coming off,” Thue Barfod, global head of seafood for Denmark’s Maersk Line, the world’s largest shipping company, told Undercurrent.

Shipping companies added a surcharge of around $1,000 per container to offset additional costs caused for shipping companies dealing with the chaos in Chinese ports at the start of the year, said Barfod. This has since been removed.

“In the first half of 2019, you could find shipping rates from Rotterdam to China below $2,000, while the market now is $4,000 to the Far East,” he told Undercurrent.

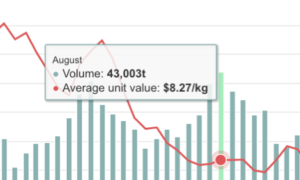

According to some sources, rates had cooled, but offers have gone up again. Taking the route from Velsen, in the Netherlands, to Qingdao in China, offers are up to $4,800 for a 25-metric-ton container, a seasoned whitefish trading source who asked to be quoted anonymously told Undercurrent.

Offers for shipping from Velsen, a significant hub for transhipping of frozen cod from the Atlantic to China, for re-processing, had dropped to around $4,000, but are up again, he said.

In late 2019, a 25t container on the same route would have been under $2,000, he said.

“Prices more or less doubled,” Klaus Nielsen, CEO of A. Espersen, a whitefish processing company with plants in Denmark, Poland, Lithuania, and Russia, told Undercurrent.

According to Nielsen, rates have started “to drop a bit from the peak”, however. “But, they are still significantly higher than before COVID-19.”

Rates went from around $2,000 for a (40-foot) container to $4,000, but have dropped to $3,500, said Nielsen. “It went from being extremely inexpensive to being slightly expensive.”

An increase has to be pushed through the supply chain, he said. “Our margins are thin, so every time you take two cents out of it, you see the business is challenged. Either the fishermen in Norway and Russia should have a reduction in price, or we should have a price that is higher to the customers because the margins we have are razor-thin.”

As Espersen is working on longer-term contracts with most of its customers, the hike will take a while to filter through to the market. “So, that will not be a pretty sight in the next three-to-six months in Europe.”

Nielsen and others feel rates are set to come down further, however.

“At the end of the line, there will be some pressure on freight rates going down because the oil price, which is a high cost for the land fleet and ocean transportation, is a fraction of what it was. Oil has dropped,” he said.

Oil prices have dived to below $20 a barrel, with inventories set high and the pandemic hitting demand.

“There is a delay with the oil price going into the freight rates of a month or three months depending on the contract,” Maersk’s Barfod told Undercurrent.

“So, the bunker [fuel] is generally set for quarter one and based on an average of different ports around the world from last month of Q3 and the first two months of Q4. Then, for the short-term contracts, there’s a trigger that if the price goes up or down more than 10%, they can implement a trigger upwards or downwards with 30 days’ notice,” he said.

Also, containers are getting back into the system after the ASF and coronavirus backlogs in China.

“At one stage, they said 1.7 million containers were out of sync in the system. So, now that China has opened up the plants that we know of are producing probably close to somewhere between 70% and up to 90%. So, of course, the goods need to flow. In theory, it shouldn’t take more than six to eight weeks; then all of these containers should be in the system. Then we should be looking at a drop in prices [for freight rates],” said Nielsen.

“I think because of the equipment crunch, the carriers, in general, have a chance of keeping a large amount of the money in their pocket. But, as soon as the peak season in the southern hemisphere is over and the equipment becomes more readily available, this will change,” a seafood sector source who asked not to be named told Undercurrent.

“There is enough equipment in the world under normal circumstances, so when this comes back, you will see then the full impact of the bunker drop as people will start competing like crazy and the rates will begin going down again, unfortunately, whether we like it or not,” he said.

First ASF, then COVID-19

Maersk’s Barfod gave Undercurrent a summary of how the situation with ASF and then coronavirus has impacted the shipping sector.

Photo credit: Maersk Line

“Roughly speaking, sometime in mid-2019, equipment shortage started becoming a situation globally, for all carriers. The reason for this was ASF in China. China sucked in products, everything they could, to replace their falling domestic pork production. So, they sourced from everywhere. Because China is also the location where everybody produces containers, it’s not really an ideal place to get a reefer container into because they have a surplus,” he said.

“So, if you get containers in, you would very likely not be able to get them out full again. I mean, they do export a lot of apples, garlic and fish, but the import ratio is much, much higher than the export ratio. So from a flow point of view, the build-up started. So, to cope with this, to get containers out again, the freight rates started increasing during the year, peaking at $2,500 to $3,000 [per container] in Q4 on the trade from Europe to the Far East/China.”

Then, on top of this, came the explosion of the coronavirus pandemic in China.

“Because of the corona crisis, the ports in China started filling up with dry and reefer cargo. The dry cargo could, in most cases, still be unloaded, while the reefer containers faced a severe lack of plugs and power points, which prevented us from discharging the cargo as intended,” he said.

For the three largest import destinations, which are Ningbo, Shanghai and Tianjin in northern China, the terminals ran out of plugs, he said.

So, Maersk’s solution was to discharge the dry cargo, then used some of its ships for floating reefer storage. “We had the reefer containers onboard outside these three ports [Ningbo, Shanghai and Tianjin].”

This was where the surcharge of around $1,000 per container, which has been removed, came into play.

“Because of this, we implemented a surcharge. But that was on top of the general rate increase. It was not done because we wanted to abuse the situation. We had to have vessels laid up in front of these points with reefers, which we couldn’t discharge because the authorities said don’t come in,” Barfod said.

“The $1,000 was implemented to recover part of that cost. And that continued until early March.”

Now China is back working; the backlog is more or less gone, he said. “So, from a congestion point of view, the crisis for the reefer containers is over. The carriers have dropped the surcharge as we don’t have reefers floating in front of Shanghai anymore.”

Even with the dropping of the charge, “rates are still fairly high”, due to the tight situation for all shipping lanes globally, said Barfod.

“What happened in a lot of the other regions, South America or South Africa, even Oceania, is there is a shortage because of the backlog in China, with the reefers which were floating on these ships or standing in port not being picked up. It messed up our flow because we have containers coming into China every week,” he said.

“And since nobody picked up the full container, we couldn’t get the empty container back to New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, or South America. So, the second wave of issues was that, in the largest exporting regions around the world, we began running out of equipment. This is still a problem that we’re having,” said Barfod.

“Obviously, the bigger the carrier, the easier it is. If you only have one service into a market and that was cut because there’s no cargo coming, then you’re pretty much screwed. But if you’re one of the larger carriers, which has two or three services coming in, then you’re not going to cut all three services in one go. So, you will still have a bit of flow of empty equipment coming in,” he said.

“These are booming export locations because March and April is the peak of fruit season. Also fish, for some destinations. So, they are booming, and because of that, you will see the freight rates have also gone up there. The reefer specialists started to put up rates. Then when we got the equipment back and wasn’t contracted, it was about supply and demand, who would pay the most.”