Study design and sample selection

We conducted a pre (01 to 15 August 2017) and post-test (10–25 April 2018) evaluation of a pilot intervention package in four schools in Dhaka Division, Bangladesh (2 urban, 2 rural). Our study team collected a list of schools in urban Dhaka from the Divisional Education Department and in rural Manikganj District from the office of sub-district level Administrative Education Officers. Field Research Assistants telephoned 200 schools and identified 40 that met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). We visited 20 randomly selected schools out of the 40, and from those purposively selected 8 schools (4 for formative research phase, 4 for intervention piloting) to include both public and private schools in urban and rural settings. The Dhaka Zonal Office, Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education; the Dhaka Divisional Office, Directorate of Primary Education; and School Management Committees (SMC) provided permission for the research to take place in the participating schools. The intervention was designed following an iterative approach which will be described in our formative paper (in progress). The findings of our formative research were consistent with results of the 2014 and 2018 Bangladesh NHS. The formative research indicated lack of MHM products, disposal and WASH facilities in schools and revealed that the schoolgirls preferred reusable cloth pads (Sultana, unpublished data), chute disposal system [11], and demonstrated that a fingerprint device would be an accurate system to measure absenteeism data (Sultana, unpublished data).

Sample size calculation

Based on the objectives, we used multiple indicators (e.g., menstruation knowledge, practices, attendance, and school achievement) to calculate the sample size. Based on clustering in schools, we determined sample size using proportions of these indicators from the 2014 Bangladesh National Baseline Survey. We assumed a minimum detectable difference of 14% for all indicators and estimated that we needed 509 respondents, using a 0.03 Intra-class correlation (ICC), 2.47 design effect [5] and 10% non-response.

Intervention delivery

The study team convened meetings with teachers, School Management Committee and Parent Teacher Association members at each participating school to provide overviews of the intervention and address questions before commencement of the pilot intervention. The team held parent conferences in the beginning of the study to make the parents aware about the components, the interventions, and the objective of the study. The intervention (Supplementary Table 1) was implemented by the schools with the support of the icddr,b study team, which comprised members with expertise in public health, medicine, health promotion and education, anthropology, and psychology.

Puberty education

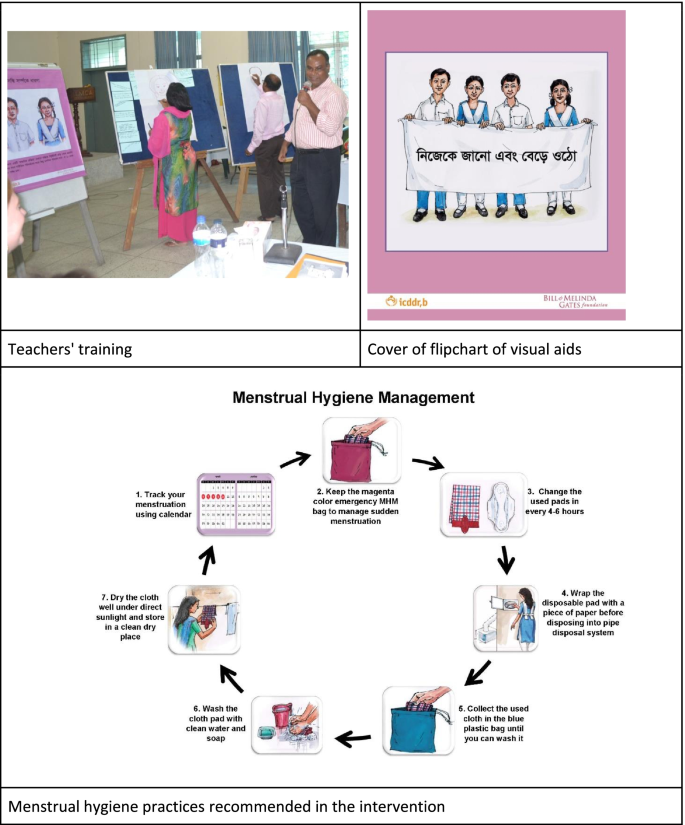

We asked the headteacher at each school to nominate at least one male and one female teacher from grades 5–10 to implement an interactive puberty education curriculum for their students. The curriculum entitled Know Yourself & Grow comprised four modules: 1) growing up, 2) reproductive systems, 3) menstruation, and 4) nutrition. We applied a training of trainers model to provide 18 schoolteachers (including headteachers) a 3-day residential training on how to deliver the Know Yourself & Grow curriculum and another 2-day mid-intervention refresher training. Participating teachers were drawn from teachers of physical education, science, or home economics. At the conclusion of the training of trainers, teachers provided individualized delivery plans for completing all modules in their schools over the 6-month pilot period. Teachers delivered the content of the four modules to their students in varying numbers of sessions according to what was feasible in their context. We provided each teacher with a teacher’s manual, locally illustrated flip charts to use as visual aids while conducting education sessions (Fig. 1), and an electronic slide deck of the materials.

The content of the puberty education was obtained from the government approved textbooks and then expanded to include more detailed content drawn from puberty booklets that had been previously developed by Bangladesh Center for Communication Programs (BCCP). We added additional content and activities regarding the practical aspects of menstrual hygiene management, pain mitigation, and addressing menstrual stigma which was not in the existing textbooks. The intervention was developed with consent and guidance from the Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education (DSHE) and MHM Working Group. The curriculum relied heavily on participatory activities, games, and role-plays to increase comfort in discussing menstruation and reduce stigma. This provided opportunities for behaviour modelling and practicing new skills (e.g., asking for support from school staff, affixing menstrual materials to underwear, estimating next menstrual period based on menstrual cycle length, proactively supporting their peers, managing menstrual pain etc.). After the training of trainers, we also provided a 1-day orientation on the schools’ premises to orient all other teachers to the material that their students would be receiving from the intervention.

To supplement the in-class education sessions, we provided each student a set of three booklets previously developed by the Bangladesh Center for Communication Programs: one with information about adolescence and puberty, one about a boy experiencing nocturnal emission for the first time and a storybook about a girl experiencing her first menstrual period [12].

Question box

Classrooms were outfitted with a locked “question box” for students to submit questions that they felt uneasy to ask in class. Teachers were to provide answers in subsequent sessions according to the information provided in their teacher’s manual. Study team members collected all submitted questions at the end of the pilot period for documentation and provided a curated list of responses to common questions for the teachers to use as a resource in the future.

MHM packs

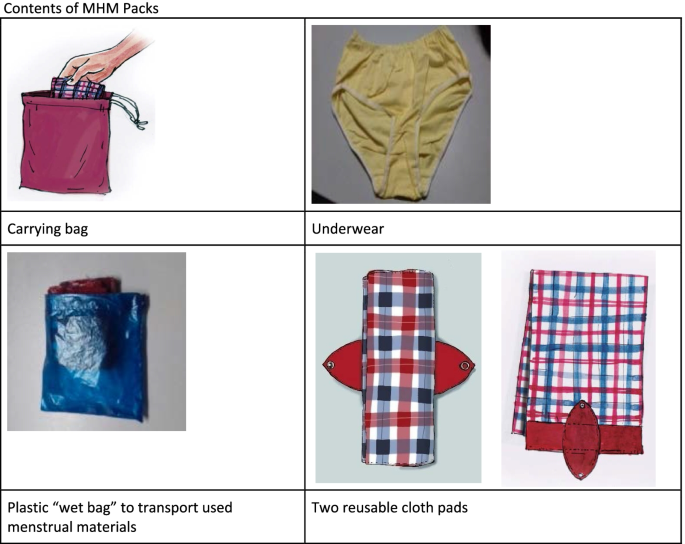

With support from school staff, study team members distributed MHM packs to every girl in grades 6–10 and to girls in grade 5 who had reached menarche. We left extra materials in school offices for students who were absent during distribution days. MHM packs (Fig. 2) comprised a carrying bag containing two reusable cloth pads (Sultana icddr,b Reusable Cloth Pad, designed by F.S. and the team, and pre-tested during the study’s formative research phase), one plastic “wet bag” to carry used menstrual materials, one underwear, and a menstrual tracking calendar (Fig. 2). We also supplied schools with a stock of disposable menstrual pads (provided by a local company named Social Marketing Company) [13] for girls who began menstruating suddenly at school and needed quick access to absorbents. The disposable pads were counted and handed to the janitors responsible for maintaining the adolescent corner of each school. We also provided them with a registrar book. If a student needed to access disposable pads, the student asked the responsible janitor who noted the student’s name, the number of pads taken, the date along with a signature from the receiving student. Study team members provided hands-on practical training to students on how to use the materials in the MHM packs at the time of distribution, and further participatory training and practice was built into the puberty education sessions facilitated by schoolteachers.

Improvements to sanitation facilities

We made minor improvements to schools’ sanitation facilities according to requirements by school students, such as fixing toilet cubicle doors, locks, and lights. We installed a chute disposal system for used menstrual materials in one female toilet cubicle in each school [11]. The chute disposal system was modelled after a design created by WaterAid in Bangladesh [14] and chosen by the students as a preferred method of disposal during the pre-testing phase of the study. We encouraged schools to provide pieces of scrap newspaper in the toilets for students to wrap used menstrual pads before disposal and soap for handwashing. We affixed posters in the girls’ toilets that illustrated the proper use of the disposal system and recommended MHM practices (Fig. 1) [11].

School gender committees

Each school formed a gender committee consisting of a female and a male student representative from each grade, teachers, headteacher, janitor, a member of the School Management Committee and the Upazila Nirbahi Officer (an administrative authority for the sub-district). Gender committees met monthly to discuss issues concerning the distributed menstrual materials, education sessions, school toilet conditions and required improvements.

Evaluation methods

Pre/post survey

We formed a separate team for survey data collection and arranged training for them. Before implementation of the pilot intervention, we selected 527 girls randomly from the participating schools’ rosters (out of those present on the day) in grades 5 to 10 to participate in a baseline survey. After 6 months of piloting the intervention package in the 4 schools, 528 randomly selected girls, selected similarly from schools’ rosters from grades 5 to 10 participated in the endline survey. We tried to select equal number of students from each grade from the rosters. We administered a tablet-based structured questionnaire for data collection.

Outcome measures

We assessed the intervention package’s acceptability and feasibility by reporting intervention uptake measures, particularly whether girls received and used intervention materials. Secondary outcomes included changes in knowledge about menstruation and recommended menstrual management behaviours; menstrual care practices; girls’ perceptions of their environment, practices, and comfort; and self-reported school absenteeism during most recent menstrual period.

We assessed knowledge about menstrual physiology on five indicators and we reported how many girls responded to them correctly. Knowledge of recommended menstrual management practices was based on four indicators, and we reported how many girls responded to them correctly. Girls’ perceptions of their environment, practices, and comfort were captured by using Likert items.

Data management and analysis

We reported prevalence difference (PD) to measure the intervention uptake and other outcomes. Intervention effect on binary outcomes was estimated by comparing endline versus baseline measures, using prevalence differences (PD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated using fixed-effects logistic regression. Effects on continuous outcomes were similarly assessed with fixed-effects linear regression to estimate the mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We adjusted for clustering (schools) effect using Sandwich estimator. For data captured using Likert items, we calculated a Chi-square test for linear trend (Cochran–Armitage test for linear trend) [15] to examine changes in these ordinal variables from baseline to endline.

Stakeholder engagement

We formed an “MHM working group” in June 2017 involving stakeholders from the Ministries of Education, and Health and Family Welfare; Directorate General of Health Services; Directorate of Primary, Madrassa, Secondary and Higher, and Technical Education; Education Engineering Department; Department of Public Health Engineering; Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU); Shornokishoree Network Foundation; and NGOs working on MHM issues. The working group intended to involve relevant stakeholders in the development of the pilot intervention and to motivate educators and policymakers in Bangladesh to implement a nationwide menstrual health and hygiene strategy. We held quarterly meetings to inform members of study updates and discussed ways forward.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of icddr,b in Dhaka, Bangladesh. We sought written approval from Directorate of Primary Education, Directorate of Secondary and Higher Education, and School Management Committees (SMC) of the participating schools for the research to take place. The study team convened meetings with Headmaster, teachers, School Management Committee and Parent Teacher Association members at each participating school to provide overviews of the study and addressed questions before commencement of the pilot intervention. We obtained written informed assent from the students and the schoolteachers provided written informed consent for the student’s participation as their guardians (in loco parentis). Each students were informed about the purpose of the study, data collection procedures and time requires for the survey, risks and benefits of participating in this study, privacy, anonymity and confidentiality of the data before beginning the questionnaire. Additionally, they were reminded that they could withdraw their participation at any time or refuse to answer any question they did not want to answer.