In Germany, health policy is mainly operated through the federal states and their communities. During the pandemic, the local health departments play a key role in prevention of outbreaks and the containment of infection chains. They are in direct contact with the population and the management of facilities such as nursing homes, as well as with the federal state governments.

After the Department of Public Health Neukölln was informed that a volunteer worker of NH01.a tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, the first containment measures were implemented in close consultation with the management of the nursing home. Here, the good cooperation and close communication between the management and the health authority proved to be essential for successful containment strategies. Nevertheless, a total of 61 people got infected in connection with this outbreak, thirteen of them died. So, the question arises which lessons can be learnt. Especially, which measures have proven themselves to be helpful, which decisions should have been made differently and which factors make outbreaks in nursing homes so difficult to control.

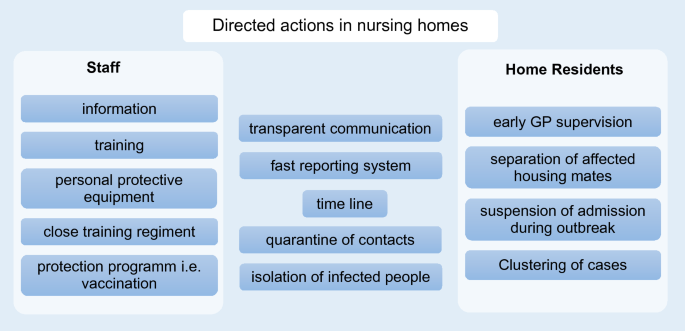

Nursing homes are among the most vulnerable institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic when vaccination programs were not implemented. A large proportion of deaths from COVID-19 are related to outbreaks in nursing homes15. This is due to shared accommodation, common activities and the demographic composition of their residents: they often are frail or suffer from pre-existing conditions, which is associated with severe disease progression1,16,17. Depending on the degree of care required, close physical contact with caregivers is inevitable. In the first outbreak in a Neukölln nursing home, 13.3% of all NH01.a residents died from COVID-19. Other outbreaks in nursing homes report an even higher mortality: Graham et al. report a mortality rate of 26% among residents in four British nursing homes18. In two nursing homes in King County, USA, 26% and 27.2% of the residents died in March 202019,20. Based on the experience with the outbreak at NH01.a, outbreaks at NH02 and NH03 were contained more quickly, even though these two homes had at least twice as many residents as NH01.a. Measures that proved effective in the outbreaks described are shown in Fig. 13.

Compared to the two previous years, mortality during the outbreak at NH01.a was significantly higher. No significant differences in mortality between the relevant periods of 2018, 2019 and 2020 can be observed in NH01.b. Thus, it can be assumed that excess mortality in NH01.a is due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The infected male residents, in particular, showed a high mortality rate, in NH01.a their mortality rate was at 80.0% and in NH03 at 50%; both higher than that of infected female residents. In regard to all residents and all staff of the three homes, men had a lower risk of infection (RR 0.64, not significant), but their risk of death in case of infection was twice as high as that of women (RR 2.01, not significant) (Fig. 8). Due to the small number of cases no conclusion can be drawn from our analysis for a generally higher mortality. Nevertheless, since Graham et al. also report a significantly higher mortality risk in men in their analysis of three hundred and ninety-four SARS-CoV-2 positive nursing home residents, these data can be interpreted as indicating greater vulnerability among older men18.

SARS-CoV-2 is difficult to contain because, among other reasons, asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic infected persons can already spread the virus21. When investigating an outbreak in a nursing home in King County, USA, Kimball et al. identified 23 residents with positive RT-PCR tests22. Of these, only ten (43%) had symptoms: eight had symptoms typical of COVID-19 and two had atypical symptoms. However, 13 (57%) of the residents tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic at the time of the swab. Of these, ten residents developed symptoms in the following 7 days22. In another nursing home in the same county, the situation appeared similar: of the residents who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 35% had specific symptoms, 8% had non-specific symptoms, and 56% were asymptomatic19. In the UK, 65.2% of 126 nursing home residents who tested positive developed no symptoms, while a further 19.8% showed atypical symptoms such as confusion, anorexia and gastrointestinal complaints18. According to Stall et al.17, frail people are more likely to show atypical symptoms such as delirium, falls, and function decline. Based on the knowledge that symptoms can be absent or atypical despite contagiousness, the aforementioned outbreaks were handled in such a way that all residents with direct contact to diseased or positively tested persons were quarantined by the public health department until a negative PCR test result was obtained. In addition, new admissions and visits by relatives were temporarily suspended when the first infection became known. Residents and staff members were tested weekly for SARS-CoV-2. Due to the spatial and organizational interdependence with NH01.a, residents and staff members of NH01.b were also tested three times at intervals of about 10 days. The immediate separation of NH01.a and NH01.b proved to be a successful strategy to protect NH01.b from the introduction of the virus. The separation of the two nursing homes was accompanied by spatial and organizational measures. On the spatial level, a hygiene lock was installed in the kitchen in NH01.a, which is used for the preparation of food in both (and two additional) facilities.

It is of great importance to train not only the nursing staff sufficiently, but also the service personnel, and to make sure that employees with other first languages get the essential information according to their language skills. Therefore, like the nursing staff, the service staff was also trained in extended hygiene measures and informed by corresponding information material. The latter included brief videos in order to inform international employees who did not speak the German language sufficiently.

Directed actions and stakeholder compliance

All these measures, especially testing, physical distance and quarantine, require compliance from all parties involved. Compliance was good for most residents and staff members. The training and information materials for the staff members, as well as transparent communication with the residents and their families by the facility managements were important. However, in the case of the outbreak in NH01.a it was problematic to enforce contact restrictions with the neighboring nursing home for those residents who could hardly be swayed by reason due to cognitive limitations. This was the case for three residents of NH01.a with positive test results and one resident of NH01.b who had direct contact to infected residents of NH01.b. Although restrictions on freedom are a fundamental encroachment on personal rights, which are anchored in the German constitution, a court order based on the Infection Protection Act was issued to protect the residents of NH01.b11,23. This provided that the three persons concerned, were allowed to be detained in their living quarters against their free will. In the case of such coercive measures, it is of great importance that adequate care is provided for the detained persons. This is especially true for people with cognitive disabilities such as dementia, for whom isolation in a room can be incomprehensible and very stressful22. In the case described here, the persons concerned received intensive care from additional nursing staff during the quarantine. Due to the duration of the judicial assessment of the situation, 8 days elapsed from the time of positive test results, in which the persons concerned did not comply with the quarantine regulations. Even if in this particular case the virus was not introduced into NH01.b as a result of this delay, the lesson learned of this experience is that it is important to draw up a plan in advance of an outbreak, defining and outlining measures to be taken in such cases, in order not to lose valuable time in case of an emergency.

Healthcare professionals caring for COVID-19 patients are at increased risk of self-infecting and spreading the infection to other parts of the facility or to their private environment13. Several measures have been taken to prevent the infection of the healthcare staff. The RKI recommends not only to isolate the infected, but to divide the affected nursing home into an infectious and a non-infectious area13. In the affected nursing homes described here, this was done by having some of the residents change rooms and one area reserved for infected residents who were cared for by the same pool of nursing staff. In NH01.a, this happened two and a half weeks after the infection of the index case became known. In retrospect, considering the high number of infected residents and nursing staff, it seems possible that the decision to take this measure should have been taken earlier, as was accordingly done in the subsequent outbreaks at NH02 and NH03.

To avoid exposing too many physicians to the risk of infection when dealing with infected home residents, a collaboration with a nearby general practitioner who cared for all cases in the nursing home during the outbreaks proved effective.

Furthermore, it is of great importance that PPE is available to the staff in situations of contact with infected residents. Therefore, one of the first measures taken by the public health department was to equip the nursing staff with PPE, which was lacking due to supply bottlenecks at the beginning of the pandemic in Germany. However, experiences from a US study showed that even trained nursing staff is not fundamentally experienced in the correct use of PPE22. Because this was also found in NH01.a, the first outbreak in Neukölln, the management of the nursing home carried out training courses on the extended hygiene measures with the staff.

With regard to contact person management, the department of public health Neukölln followed the guidelines of the RKI. These distinguished three categories of contact persons depending on the duration and intensity of contact with the infected person. Nursing staff of COVID-19 patients without sufficient equipment with PPE are considered contacts of the first category and are quarantined. However, nurses who are adequately equipped with PPE and who use PPE correctly belong to category III and may work under safety precautions13. This is of great importance to maintain the functioning of the nursing homes, especially if a part of the nursing staff is already infected and absent for a longer period of time15. In exceptional cases, however, quarantine was imposed on asymptomic nurses until a negative PCR test result was obtained. These nurses lived in other districts than Neukölln. Since the federal structures in Germany mean that other public health departments are responsible for these districts, measures are not consistent. In order to compensate for the lack of staff due to quarantined and diseased nurses, leased employees were hired. Since sufficient and well-trained staff is important to ensure the functioning of the nursing home and to keep the number of infections as low as possible, it is important to employ such additional staff for a longer period of time.

In retrospect, the following measures can therefore be assessed positively: It was important to have transparent communication and cooperation between the public health department, the nursing home’s management, the service and nursing staff, the residents and their relatives. This included a flow of information and staff training. Immediate measures such as isolation of the infected, quarantining of contacts among the residents, equipping the staff with PPE and close-meshed testing instead of quarantining nursing staff proved to be effective in fighting the virus while maintaining services. Particularly in the case of pathogens which, like SARS-CoV-2, are unknown or little researched to this date, it is important that the scientific findings are continuously observed, especially by the health authorities, and that measures are adapted flexibly to the current state of knowledge.

However, in order not to waste valuable time, pandemic plans should be drawn up in advance by the nursing homes in cooperation with the local health authorities, which also take into account how to deal with cognitively impaired residents. In addition, a structured documentation system is needed in the health authorities in which all data relevant for containing the outbreak, such as test results and measures taken, are systematically stored and accessible to the staff of the pandemic team. The described outbreak took place at an early stage in the first wave of the pandemic in Germany 2020, so that pandemic teams had to be newly formed and new structures had to be established. As a result, the many people initially involved used different systems for storing data before systematizing it, which can lead to incomplete or incorrect documentation. A faster reporting system that allows coordination with neighboring districts is also lacking in Berlin to date. A backlog demand can be observed here, which is due in particular to the fact that health authorities in Germany have been poorly equipped financially and in terms of personnel in recent years. This has had a negative impact on the degree of digitization, among other things24. The same applies to nursing homes, which are often understaffed because many vacancies cannot be staffed due to skills shortages. Hygienic work in nursing requires time, as Stahmeyer et al. have demonstrated, using the example of a German intensive care unit25. For this reason, a health care system must ensure that care and health facilities can be adequately staffed. These are overarching measures that cannot be solved in the short term, but whose importance become obvious during the pandemic. In Neukölln, during the pandemic, an impending shortage of personnel in facilities is recorded at 2-week intervals by the public health department in order to be able to intervene in time. Through a platform initiated by the Berlin government, nursing staff can be found in situations of bottlenecks26. This aims to reduce the risk of nosocomial infections caused by overworked healthcare workers. In order to avoid shortages in supply, it can also be useful to pursue previously uncommon approaches. In Toronto, Canada, a partnership between an affected nursing home and a nearby hospital has proven successful. The hospital has agreed in advance to provide personnel, equipment and clinical expertise in case of an outbreak17. Furthermore, nursing homes and health authorities should decide on temporary restrictions for visits and community activities depending on the local infection situation. Kimball et al. also recommend the wearing of face masks by nursing home residents and regular cohort testing among residents and caregivers22. However, the latter should be discussed in the context of testing capacity and regional infection rates, as low prevalence increases the percentage of false positives27. This has to be considered especially in cases where the rapid antigen point-of-care tests are in use. As of September 2020, 47.1% of COVID-19 cases in Neukölln, are connected to outbreaks in nursing homes. However, there is an observable trend that fewer nursing homes are affected by outbreaks during the ongoing pandemic. This can be interpreted as a sign that lessons have been quickly learned from the experience of the first outbreaks and that preventive measures as well as the vaccination program are successful.

This report describes an outbreak in a nursing home under its specific conditions. Therefore, the experiences cannot be fully transferred to other outbreak events. However, our analysis can solely give an impression of what directive measures could be effective and what aspects should be considered when deciding on measures. Due to the small number of cases, the information value of the statistical analyses is limited. So far there are few studies on COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes. To substantiate these statements, evaluations of data from a larger number of nursing homes would be necessary.