Review process and outcomes

Our initial search yielded 1596 publications, of which 352 came from PubMed, 1133 from Scopus and 111 from Web of Science. After removal of duplications, we were left with 1053 publications. After scanning titles and abstracts, while applying our eligibility criteria, we were left with 114 publications. We selected 37 publications after reading the full text of the publications. In April 2021, we re-searched the three search engines for additional publications. This search yielded 2 more studies. Based on snowballing (i.e., scanning references of included articles) we added 5 more studies, bringing the total publications included in our literature review to 44. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the selection process of the included publications in this literature review.

Characteristics of the pooled procurement mechanisms

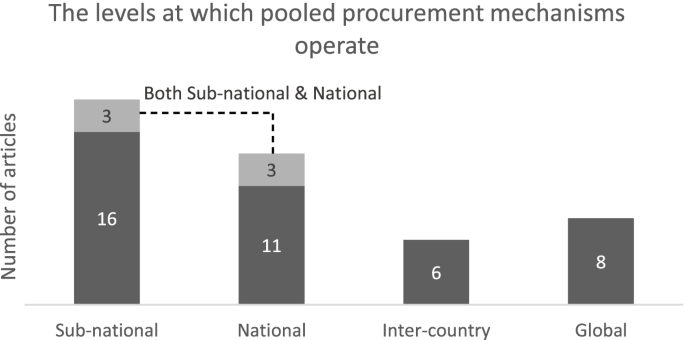

We extracted three important general characteristics of the pooled procurement mechanisms described in the 44 included articles. First, we identified the operating level of each pooled procurement mechanism (i.e., sub-national, national, inter-country and global). Figure 2 shows that the majority of the articles focused on pooled procurement mechanisms on sub-national level, followed by 11 at national level, 8 global level, and 6 inter-country pooled procurement mechanisms. 3 articles described or compared multiple pooled procurement mechanisms operating on both sub-national and national levels.

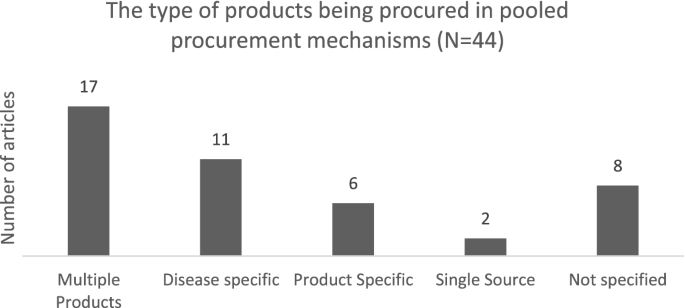

Second, we identified the type of product that was being procured by the pooled procurement mechanism described in the publication. These product types were categorized into disease specific (e.g., TB, HIV, Malaria), product specific (e.g., vaccines, orphan medicines, paediatrics), multiple products (e.g., essential medicines), single source (e.g., patented products), or as “not specified” if details on the product type were lacking. Figure 3 shows that the majority of the articles focused on pooled procurement mechanisms that procured multiple products, mainly essential medicines. This was followed by 11 articles on disease specific products, such as antiretrovirals (ARVs), cancer-medicine, hepatitis C medicine and antimalarials. 6 articles focused on product specific pooled procurement mechanisms, mainly vaccines.

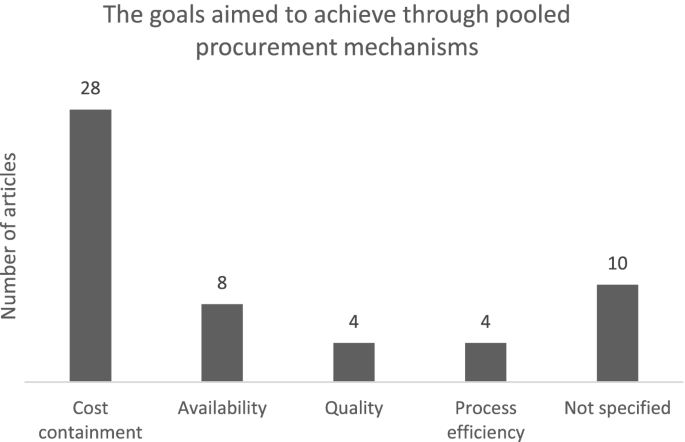

Third, we identified the goals that each pooled procurement mechanism tried to achieve. These goals were based on the authors’ description in each publication. We grouped these goals in four main categories: 1) to contain costs, 2) to improve quality, 3) to increase the efficiency of the procurement process and 4) to increase the availability of medicines or vaccines. The articles that did not mention any goal were grouped under ‘not specified’. Also, some publications provided multiple goals. We added the articles containing multiple goals for pooled procurement to each goal category separately. Hence, the total number of articles does not add up to 44. Figure 4 shows that 28 articles mentioned cost containment as a goal for setting up the pooled procurement mechanism, followed by 8 articles that mentioned increasing availability of health products as the goal to achieve. 10 articles did not specify the goal for setting up the pooled procurement mechanism.

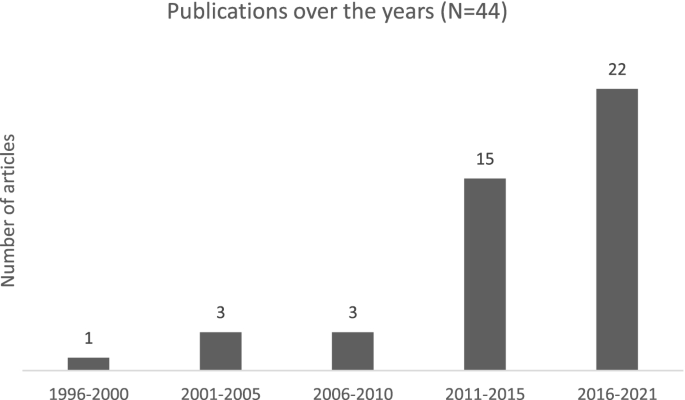

In addition, we observed an increase in the number of publications on pooled procurement mechanisms in recent years. Figure 5 shows that 37 out of the 44 studies that met our eligibility criteria were published in the last 10 years.

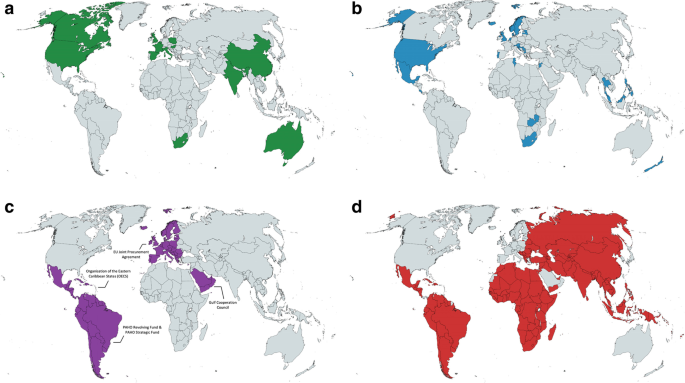

Furthermore, we have generated 4 world maps with varying pooled procurement operating levels to provide a global overview of the pooled procurement mechanisms described in the included studies. Each world map shows the countries that procure through a pooled procurement mechanism on a particular operating level. Fig. 6a shows the countries mentioned in empirical studies that have a pooled procurement mechanism on sub-national level, Fig. 6b shows the countries mentioned in empirical studies that have a pooled procurement mechanism on national level, Fig. 6c shows the countries mentioned in empirical studies that have a pooled procurement mechanism on inter-country level, and Fig. 6d shows the countries that procure through the global health organizations included in our review (i.e., Global Drug Facility, Global Fund, UNICEF Supply Division, and The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East).

a Countries that have sub-national pooled procurement mechanisms included in our review. b. Countries with national pooled procurement mechanisms included in our review. c. Countries with inter-country pooled procurement mechanisms included in our review. d. Countries that procure through global health organization pooled procurement mechanisms included in our review. Created with mapchart.net

This global overview shows that empirical studies of sub-national and national pooled procurement mechanisms have mainly focused on middle- and higher-income countries. There are very few empirical studies describing inter-country pooled procurement mechanisms, especially of failed attempts, in the English language peer-reviewed literature.

See Additional file 3 for a table with a detailed description of the characteristics of the pooled procurement mechanisms included in our study.

The remainder of this Results section is organized around the three categories of key actors that play a role in a pooled procurement mechanism: the buyers, the pooled procurement organization that carries out the actual procurement, and the suppliers. For each category of key actor, we identified elements essential for the successful implementation and functioning of pooled procurement mechanisms. While measures of success may vary, we classify these elements as essential because they appeared present in most or all well-functioning pooled procurement mechanisms, while where they were described as absent or incomplete, the mechanism often experienced difficulties or inefficiencies as a result. Our analysis concludes with an overview of pooled procurement’s main outcomes that emerged from our analysis of the literature.

Buyers

In the empirical studies, we found several elements that were essential at the level of the individual buyer, which ranged from a group of health facilities at the sub-national level to national level governments. The elements that emerged from the empirical studies included the buyer’s degree of technical capacity, its level of financial capacity, and the presence of compatible laws and regulations.

Sufficient technical capacity of the individual buyer

A certain degree of technical capacity, which includes the presence of qualified human resources and the accuracy of demand forecasting, was required for all buyers to participate efficiently in a pooled procurement mechanism [26, 27]. This was even the case for buyers for which the motivation to participate in a pooled procurement mechanism was a result of lacking technical capacity and inefficient procurement processes [28].

In some cases, the lack of sufficient, dedicated and qualified procurement staff resulted in other staff having to take over the task of procurement on top of their existing responsibilities. For example, a case-study focusing on the pooled procurement of Italian hospitals in Tuscany noted that mainly pharmacists were responsible for procurement related activities, compromising their clinical activities [29].

As mentioned above, another important aspect of technical capacity that was required at the individual buyer level to increase procurement efficiency was accurate demand forecasting. Demand forecasting is a crucial step to determine the appropriate quantity of each product at a given time to be procured. Underestimating demand can result in shortages, while overestimating can result in wastage. To procure the right quantity of a certain product at the right time, reliable demand data has to be provided by the buyer [11, 30, 31]. However, even in the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States’ inter-country pooled procurement mechanism, accurate demand forecasting proved to be challenging at times [32]. The authors provided several reasons for the inaccurate forecasting, including inadequate stock management, formulary changes, marketing of new products by suppliers, partial shipments from previous orders and longer lead times. In another study, demand forecasts in 3 out of 5 Indian states included in the study, were based on overestimating last year’s consumption data by 10–15% as a result of the lack of qualified staff. This lead to wastage of funding, resources and storage space [33].

Some global health organizations, such as the Global Fund, have been trying to increase technical capacity by providing technical support and capacity building activities, including demand planning, quality testing, warehousing, logistics, monitoring and financial management [27, 34, 35]. However, the empirical studies included did not report on the outcomes of this capacity building attempt in buyer countries.

Sufficient financial capacity of the individual buyer

Buyers also needed sufficient, timely and sustainable financial capacity to procure through the pooled procurement mechanism. For example, some of the public hospitals in Mexico that rely on centralized procurement of the Ministry of Health for cancer medicines experienced shortages due to insufficient funds at the hospital and ministerial level [36].

Buyers lacking sufficient financial capacity were in some cases eligible for external funding from donor agencies, foreign ministries or other global (health) organization to procure their products through the mechanism [37, 38]. We identified a few examples of buyers, mainly participating in third-party global health organization pooled procurement mechanisms, that rely on external funding to procure health products. For example, low income countries receiving GAVI-funding to procure their vaccines through UNICEF [38], GAVI-eligible Latin American Countries to procure the Rotavirus vaccine through the PAHO RF [37] and recipient countries that receive funding from the Global Fund to procure HIV, Malaria and TB medicines [34].

Compatible laws and regulations at the individual buyer

Buyers should also create a legal basis that allows for pooling between health facilities or countries. This means that national laws and regulations should be compatible with (international) pooled procurement and import of health commodities. Compatible laws and regulations were particularly relevant for inter-country or global pooled procurement mechanisms. For example, the adoption of the Decision on cross-border health threats (1082/2013/EU) by the European Parliament provided the required legal basis for the Joint Procurement Agreement to be negotiated [28]. In the example of pooled procurement of ARVs in Latin America and the Caribbean, the participating countries paid higher prices than the negotiated reference price, which was partially due to incompatible legal frameworks to comply with the negotiated technical and administrative conditions [30]. One specific example of this are the national laws in Mexico. Chaumont et al. [39] mentioned that national laws in Mexico limit the import of patented products to only the patent holder or an authorized licensee. This law prevents public institutions in Mexico to procure patented ARV medicines more cost-effectively through an international pooled procurement mechanism, such as the PAHO Strategic Fund. Other examples, both on sub-national and national level, underlined the importance of a legal basis for the functioning of pooled procurement mechanisms. In Italy, adaptations to national laws increased the legal mandate of regional purchasing bodies such as signing framework agreements [40], while the lack of a solid legal basis in China was seen as a potential reason for stakeholders to question the legality of pooled procurement in the long run [41].

Relative homogeneity at the inter-buyer level

When several buyers come together to procure through a buyer’s pooled procurement mechanism (as opposed to a mechanism outsourced to a third party), the relative homogeneity of the buyers’ characteristics at the inter-buyer level appeared to be important for the functioning of mechanism. These buyer characteristics included the joint need for specific products, the market size and demographics. The Eastern Caribbean Drug Service, now called the Organisation of the Eastern Caribbean States Pharmaceutical Procurement Service (OECS/PPS), is an example of an inter-country pooled procurement mechanism where nine fairly similarly sized island nations pool together to increase their collective market size [32]. These nations shared similarities in financial capacity and epidemiological needs. They also benefit from a single central bank and currency, and have developed a joint Regional Formulary and Therapeutics Manual [32].

The level of homogeneity of the buyer characteristics directly influences the ability to align motivations, goals and purpose of the pooled procurement mechanism among buyers [42]. The more divergent buyers’ characteristics are, the more likely it is that the buyers’ motivations to participate and goals will differ, or even conflict. In the case of a third-party organization pooled procurement mechanism that procures on behalf of its buyers, the motivations, goals, needs and purpose should be aligned between the individual buyer and the third-party organization [43]. This became also apparent in another example of health centers in Quebec, Canada. In addition to diverging goals between buyers, the goals of some of the participating health centers (i.e., buyers) were misaligned with the goals of the pooled procurement organization (i.e., purchasing group) [44]. According to some of the participating health centers, the third-party organization lacked flexibility to adapt to the needs of the health centers, restricting the scope of the products being procured.

Shared values for productive collaboration

Multiple articles underlined the importance of some essential general values that facilitate the process of productive collaboration and alignment. These values included sharing data and information in a transparent way [11, 28, 30, 31, 43, 45, 46], managing positive relationships [42,43,44], good communication and maintaining sufficient trust levels, both among buyers and between buyers and the pooled procurement organization [32, 42, 44,45,46,47]. However, the empirical studies provided limited description of the specific activities required to achieve these values.

Pooled procurement organization

We identified several elements that the pooled procurement organization, which is an organization that is set up to carry out the actual procurement, had to meet to procure health products successfully. The elements that emerged from the empirical studies included the pooled procurement organization’s level of financial capacity to both carry out procurement and cover organizational expenses, the organization’s degree of technical capacity, and the organization’s operational values and principles.

Sufficient financial capacity of the pooled procurement organization

Like buyers, the pooled procurement organization also needs sufficient, timely, and predictable budget. This budget is required to both procure health products, as well as to cover organization expenses [33]. The empirical studies highlighted two main sources for the pooled procurement organization to secure sufficient, timely, and predictable budget to carry out pooled procurement: through buyers and through donor funding.

The OECS/PPS provides an illustrative example of buyer-financed budget. The island nations, which share a common currency, established a revolving fund at the inter-country level, managed by the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank. This financing structure allowed all participating countries to commit one third of their annual pharmaceutical budget to the mechanism, even before its establishment [32]. This was a clear demonstration of deep political commitment of the buyers.

International global health organizations, such as the Global Fund and GDF, rely mainly on donor funding to aggregate sufficient, timely, and predictable budget to carry out pooled procurement [35, 48].

Likewise, sufficient and timely budget is needed to cover organizational expenses. Azzopardi-Muscat et al. [28] underlined that the lack of a dedicated central level financing to cover organizational expenses within the European Union Joint Procurement Agreement was a potential threat to the sustainability of the program. As shown in Table 2, we identified five different ways of covering organizational expenses: service fees paid by buyers; service fees paid by suppliers; membership fees paid by buyers; membership fees paid by suppliers; and external donor funding. For each way of financing, an example from the empirical studies is provided. Some mechanisms cover their organizational expenses through a combination of these payment forms.

Sufficient technical capacity of the pooled procurement organization

The functioning of pooled procurement mechanisms heavily relied on the technical capacity present at the level of the pooled procurement organization. To function successfully, the organization needed to have sufficient resources to carry out or outsource procurement tasks such as assessing product quality, aggregating demand data, tendering, and establishing an efficient payment mechanism. For example, the GDF has a dedicated secretariat with clear roles and responsibilities. For specialized tasks such as supply and quality-assurance, the GDF outsources its tasks to external agents on a contractual basis. According to Kumaresan et al. [35], the GDF achieves higher operational efficiencies through outsourcing to external agents with expertise. In addition, Chaudhury [45] underlined that committed staff and sufficient technical capacity as a result of ongoing training programs were among the critical success factors for the functioning of Delhi’s essential drug program, which includes its pooled procurement mechanism.

The lack of sufficient technical capacity to assess the supplier’s ability to fulfil contracts at the level of the organization led to decreased availability of medicines in some local areas in China [50].

In addition to outsourcing, pooled procurement organizations have tried to increase qualified human resources in two ways: by pooling the available expertise and staff among its buyers to create expert networks [28, 47]; and by pooling resources to attract expert staff from outside the buyers pool [40].

Independent operations of the pooled procurement organization

The concentration of authority in a single organization can be a double-edged sword. As the intermediator that carries out the actual procurement, the pooled procurement organization centralizes data, bargaining power, and procurement decisions. On the one hand, this allows for increased efficiency. On the other, it might make the organization vulnerable to influences of conflict of interest and even corruption if there are no checks and balances in place to guarantee independence and transparency of the organization and its staff. Several studies stressed that relative independence of the pooled procurement organization, which may limit the potential for conflicts of interest, is essential to function and achieve its intended outcomes [11, 27, 28, 33, 36, 40, 51]. In many Chinese provinces, pooled procurement organizations have not been operating independently [51]. These organizations were often affiliated with the health bureaus, responsible for public health in the county. Experts in the study [51] hypothesized that concentration of procurement power at the central level could facilitate bribing, since fewer people and organizations are involved in the process. Baldi and Vannoni [40], however, demonstrated that areas in Italy with higher levels of corruption or lower levels of institutional quality benefited most from pooled procurement’s price reduction. The authors speculated that a central authority with high levels of institutional quality might be protected more effectively from influences of corruption and local favoritism of suppliers because larger tenders provide fewer opportunities for bribery.

The empirical studies also mentioned the importance of the organization’s standardized and transparent procedures. Singh et al. [33] underlined that transparency was needed at all levels of procurement. The procurement organizations in Tamil Nadu and Kerala established autonomous pooled procurement organizations. They also involved multiple stakeholders throughout their procurement, which contributed to open and transparent procurement processes. Separating the responsibilities of staff, such as awarding winners and paying suppliers, also reduced the vulnerability to conflict of interest. Shi et al. [51] added that the procurement criteria set by pooled procurement organizations in China were often not scientifically based and difficult to quantify, leaving room for ambiguity and possible corruption. Wafula et al. [27] mentioned that the majority of countries receiving funding from the Global Fund opposed enforced procurement through the Global Fund’s pooled procurement mechanism. Potential valid reasons for recipient countries to oppose enforced participation were the already existing sufficient technical capacity and experience at procurement agencies [27], or the creation of over-dependence on external organizations, which might weaken health systems [34]. Although not validated in the study [27], another potential reason provided by the authors for opposing enforced participation might have been self-interest driven by procurement staff. Through enforced participation, procurement staff in recipient countries would lose their decision-making power, and possibly their channel to obtain illegitimate income.

Suppliers

Healthy supplier competition

In addition to buyers and the pooled procurement organization, suppliers are a fundamental category of actors that play a crucial role in the functioning of pooled procurement mechanisms. The articles pointed out a significant trade-off between short-term economic benefits and potential long-term availability issues.

On the one hand, the pooled procurement mechanism needs a healthy competition of suppliers in the market that are willing to participate in the tender. 17 of the 44 included studies have stressed the importance of supplier competition to sustain a pooled procurement mechanism. Sufficient supply-side competition has been linked with lower medicine and vaccine prices [48, 52,53,54], whereas the price-reducing effect of pooled procurement mechanisms reduced in monopoly markets (i.e., single source products) [55]. Malaysia’s policy to prefer local generic suppliers over international suppliers also reduced supply-side competition, which might reduce the pressure for local suppliers to lower prices [56].

On the other hand, a few studies [41, 42, 50, 53, 57] have mentioned pooled procurement’s potential influence on reducing competition on the supply-side. The reason given is that pooled procurement mechanisms aggregate demand, resulting in larger but less frequent tenders. The extensive pressure on prices might result in a race to the bottom for suppliers, driving out mainly small and medium suppliers. This might erode market competition, which eventually leads to shortages and an increase of medicine prices in the longer run. Although this explanation might be plausible, none of the included studies have demonstrated pooled procurement’s supplier competition reducing effect in practice. This lack of empirical evidence was also mentioned by Toulemon [58] and Burns & Lee [59].

Incentives to supply

To increase supplier competition, the pooled procurement organization needs to offer suppliers sufficient incentives to participate in the mechanism. Several supplier incentives have been mentioned in the literature, such as creating a sufficient market size [11, 28, 32, 38, 44, 48, 49, 60]. One way of increasing the market size for certain products is through unifying medicine formularies [32, 60]. Other supplier incentives included adopting an efficient and prompt payment mechanism [11, 28, 32, 33, 37, 38, 61], adopting standardized and transparent procurement procedures [32, 45, 61], issuing long-term framework agreements [38, 43, 57], aggregating accurate demand forecasts provided by the buyers [11, 31, 38], protecting intellectual property rights [31], and awarding multiple winners for tenders [11, 32, 50].

Outcomes of pooled procurement mechanisms

Figure 4 shows that there were 4 main goals for establishing a pooled procurement mechanism, as reported by the authors: to contain costs, to increase availability, to increase quality and to increase the efficiency of the procurement process. Similarly, the reported outcomes in the papers mainly focused on these 4 categories. However, the outcome reported in a paper did not necessarily match the main reason for establishing the mechanism. Hence, the number of papers provided in the following paragraphs do not match the numbers in Fig. 4.

Prices of medicines or vaccines

29 empirical studies reported on the effect of pooled procurement on prices or costs of medicines or vaccines. The majority of the papers observed a price reduction after introduction of pooled procurement [11, 26, 29, 32, 35, 40, 41, 45, 48, 52, 53, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

For example, Shi et al. [51] mentioned that pooled procurement at the provincial level in China reduced medicine prices by around 30% in Beijing, 41% in Hebei and 46% in Shandong. Perez et al. [46] even observed a 90% reduction of hepatitis C medicine prices in Colombia after procuring through the PAHO Strategic Fund, an inter-country pooled procurement mechanism. The authors attributed this price reduction to a combination of factors, including a comprehensive design and implementation strategy leading to the alignment of needs between various stakeholders, and the adoption of laws and regulations. Dubois et al. [55] noted that the pooled procurement mechanisms included in their study led to a reduction of medicine prices by 15% on average. They hypothesized that price reduction might have been caused by the buyer’s increased bargaining power in combination with higher purchase volume. However, where supply side was more concentrated (i.e., less supplier competition), the observed price reducing effect of pooled procurement became less.

Not all studies recorded sustainable price decreases as a result of implementing pooled procurement. Prices of patented ARVs in Mexico reduced with 38% after the first round of joint negotiations in 2008 [31]. However, the price reductions between 2008 and 2013 were minimal [39], and remained on average five to six times higher for some ARVs compared to economically comparable countries [31, 39]. Adesina et al. [31] hypothesized that the initial price reduction of ARVs in Mexico might have been influenced by global trend of ARV price reductions during that time.

Zhuang et al. [54] reported that prices of category 2 vaccines in China, which are non-mandatory vaccines that require payment from the patients, increased after introduction of pooled procurement in 2016. Possible reasons were related to quality, see section on quality below.

Kim and Skordis-Worrall [34] found that the Voluntary Pooled Procurement mechanism of the Global Fund reduced the ex-works price of Efavirenz by 16.2%. However, they found no connection between transaction volume and price reduction or between market competition and price reduction. The price reduction was partially attributed to a general decreasing trend of ARV price between 2005 and 2013. Similarly, Singh et al. [33] found no connection between volume and price. The prices of some of the 32 selected medicine were higher in Tamil Nadu, which is expected to have significantly higher medicine consumption compared to Odisha, Punjab and Maharashtra.

He et al. [64] observed no decrease in medicine prices or in total health expenditure after introduction of the Centralized Procurement of Medicine Policy in Sanming, China. Prior to implementation of this policy, Sanming adopted a Zero Mark-up Drug Policy, forcing hospitals to sell medicines at wholesale price. This policy led to significant reduction of medicine expenditure in the short term. This reduction diminished after the introduction of Centralized Procurement of Medicine Policy. Potential explanations given by the authors included the existence of a form of pooled procurement before the introduction of the Centralized Procurement of Medicine Policy, and the presence of kickbacks that incentivize physicians to overprescribe medicine.

Availability of medicines or vaccines

11 studies reported on pooled procurement’s effect on availability of medicines or vaccines. Chaudhury et al. [45] observed that availability of essential medicines increased in several tertiary hospitals in Delhi after implementing pooled procurement. Similarly, Wafula et al. [48] mentioned increased availability of malaria commodities after implementation of the Global Fund’s Voluntary Pooled Procurement.

Sruamsiri et al. [65] noted significant increases of patients treated with cancer medicines in Thailand, which was used as a proxy for availability. However, the effect of pooled procurement on increased availability could not be determined, because during the same time the Thai government implemented additional pharmaceutical policies, such as issuance of compulsory licenses and price negotiations.

Chokshi et al. [61] observed that Tamil Nadu managed to find suppliers for all medicines on their procurement list, while Bihar was only able to find suppliers for 56%, 59% and 38% of their medicines in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively. Although both states pooled their procurement of medicines, the authors explained that the difference was mainly caused by the financing and distribution mechanisms in Tamil Nadu, which were much more integrated with the procurement process compared to Bihar.

In contrast, Song et al. [53] observed no increase in the overall availability of essential medicines in primary healthcare facilities after implementation of pooled procurement in two Chinese provinces, namely Shandong and Ningxia.

Procurement efficiency

17 studies reported on the effect of pooled procurement on the efficiency of procurement processes. A few studies pointed out that pooled procurement might be particularly beneficial for smaller buyers in the pool because they are expected to benefit most from increased market size, increased technical capacity, human resources and financial capacity [11, 28, 38].

Budgett et al. [66] noted increased standardization as a result of integrated procurement and information technology processes, both on national level in Costa Rica, as well as sub-national level in Victoria, Australia. Similar process efficiencies and standardizations were described in Italian hospitals in Tuscany [29], the OECS [32], the GDF recipient countries [35], the PAHO RF and in the GCC [11].

Quality of products

There were only 3 studies reporting on the relationship between pooled procurement and the quality of medicine or vaccines.

The paper of Zhuang et al. [54], referred to in the section on prices of medicines or vaccines, reported that the increase of prices of category 2 vaccine in China after the introduction of pooled procurement was potentially related to the increase of quality standards. These quality standards included the adoption of a standardized vaccine list with registered vaccines, the reduction of substandard or falsified vaccines and elimination of illegal or unregistered suppliers. The authors noted that other factors, such as purchase volume, inflation and the number of vaccine producers might also have affected the vaccine prices.

Two papers focused on the drug policy to increase access to essential medicines, adopted in 1994 by the state government of Delhi, India [26, 45]. As part of this policy, Delhi implemented pooled procurement mechanism. To secure quality, a quality-assurance mechanisms, including prequalification of suppliers, Good Manufacturing Practice inspections, testing of procured batches in accredited laboratories, and sanctions for suppliers if medicines failed quality testing were integrated into the pooled procurement mechanism. As a result, the medicines that failed quality control decreased from 1.45% in 2001 to 0.13% in 2009. This policy resulted in procurement of quality medicines for low costs in Delhi, India [26, 45].