Residential propane prices have risen sharply already this year, with the state averaging $2.21 per gallon in late November, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The current price is 71% higher than last year, when propane cost $1.29 per gallon in November, and is 92% higher than five years ago, when it was $1.15 per gallon in November 2016.

As of late November 2021, the average price for a gallon of home heating oil in South Dakota was $2.51, according to the federal government, up 68% from the same date in 2020 when it was $1.55 per gallon. The price was as low as $1.21 a gallon in March 2020.

Households that rely on natural gas for heat may see a jump of 30% in their annual heating costs, the energy administration has predicted, as natural-gas futures prices have jumped by 132% so far in 2021.

Electricity rates tend to be less volatile than prices for other fuels, and South Dakota is close to the national average of 13.31 cents per kilowatt hour of electricity, with an average rate of 12.39 cents per kWh in November 2021 compared to 12.57 cents per kWh in November 2020, according to the federal government.

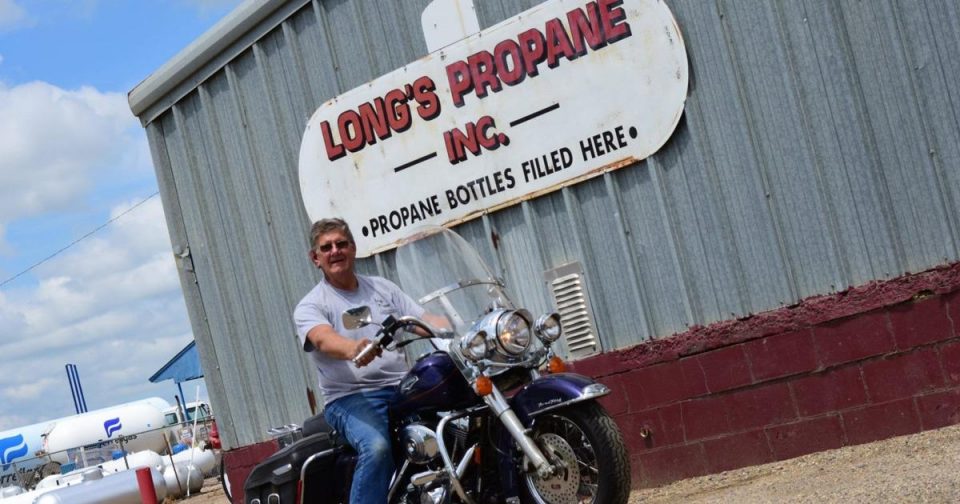

High costs for propane and other fuels are a big concern for homeowners, but also for businesses and governments that rely on those products, said Mark Nielsen, owner of Long’s Propane Service in Yankton.

“Homeowners have furnaces and fireplaces that run on propane, but a lot of restaurants do a lot of cooking and they heat water with propane,” Nielsen said. “Road construction crews use propane to make asphalt and farmers use propane to power their motors or irrigation pivots.”

Nielsen said the high prices are causing concern among many customers, especially those who buy their propane in bulk for the upcoming winter season. Nielsen and many other propane suppliers have minimum purchases of 200 gallons, which can mean a bill of $400 to $500 for a single delivery.

“It’s about double the price from last year and they’re pretty upset about it,” he said.

Nielsen said propane dealers also suffer losses when fuel prices rise, due to higher transportation costs, reduced orders from customers who can’t afford to buy in bulk, and overall lower profit margins.

“Anytime the price goes up, your margin goes down, and more people don’t pay or they have bad debt,” Nielsen said.

Maureen Nelson, a senior program director for Grow South Dakota, a community support agency that uses state and federal funding to encourage business development and provide rent and utility assistance to families in need, uses several strategies to help families stay warm and safe in winter.

Nelson is based in Sisseton, where her agency serves 17 counties in northeastern South Dakota. So far in 2021, the agency has provided more than $236,000 in rent, utility and other assistance to 619 individuals in roughly 240 households. The agency also has provided about $1.1 million in rent, utility and mortgage assistance through the South Dakota Cares housing program.

Nelson said rent assistance has been the primary need so far in the fall of 2021, but she expects the need for home fuel funding will rise as temperatures fall in the coming months.

“It’s only going to get worse,” Nelson said. “It was tough when propane or any heating cost was cheaper, and now I think you’re going to see even more families struggling.”

Inflation that has driven up consumer prices and supply-chain challenges that have limited access to goods and services are adding stress to the equation for families trying to keep homes heated.

“If your furnace does break down, it’s hard to find the people or parts to fix it,” she said. “That comes into play in rural south Dakota where you’re having to ask a repairman from 50 to 100 miles away to come out and fix that, and that’s if they have the parts they need right now.”

One major federal program, the Low Income Heating and Energy Assistance Program, or LIHEAP, provides billions of dollars each year to qualifying low-income families across the country.

In 2020, the program was allocated $3.7 billion and provided heating, cooling, weatherization and crisis assistance to more than 5.6 million American households. A one-person household can qualify if annual income is less than $25,760 or less than $53,000 a year for a four-person household.

In South Dakota, the program allocated $22.8 million in 2020 to more than 21,000 households.

Federal records show that less than a quarter of South Dakota families that qualified for assistance last year received money, likely because they did not know about the program or did not apply. Also, advocates of the program note that LIHEAP is not an entitlement program and as such is subject to the fluctuations of congressional budget approval.

In 2017, former President Donald Trump floated elimination of the program, and though Congress kept the assistance in place, overall funding has dropped in recent years.

In South Dakota and on the federal level, allocations to LIHEAP have dropped by about 18% from Fiscal 2010 to Fiscal 2020, according to the National Energy & Utility Affordability Coalition.

LIHEAP remains an important part of the safety net for low-income families that have trouble paying for utilities in South Dakota, the coalition and local advocates said. In 2020, 77% of households that received LIHEAP payments in South Dakota included at least one person who was elderly, disabled or under 6 years old.

Nelson said the federal government has provided some new avenues for assistance for families affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has eased the financial burden on some families.

Nelson urged people who face financial uncertainty to reach out to the state energy-assistance program or to local community support agencies such as Grow South Dakota to see what funding help may be available. She also counsels families to talk directly with their energy providers to see if they can agree to a “budget billing” program where payments can be spread out over time in order for people to get through a cold winter.

Nelson said Grow South Dakota and other agencies that offer utility assistance are providing a critical service to South Dakota families in need.

“It’s a great feeling when you’re able to provide that assistance, to make that phone call that I’m going to be able to fill up your propane tank today, or we were able to cover that electric bill and get your lights turned back on,” Nelson said. “It makes you feel warm inside, and that’s what agencies like mine are here for.”

Propane prices can vary significantly in South Dakota, and like gasoline prices, they tend to be higher in West River and remote rural areas. Recently, for example, retail propane cost about $2 a gallon in Yankton in the southeast and nearly $2.50 a gallon in Rapid City in the west.

The main reason all fuel prices are rising, including propane, heating oil, unleaded and diesel gases, is higher crude oil prices on the global market, said Mark O’Donnell, partner with Meridian Liquids Partners, a wholesale propane distributor in Yankton.

In the current crude oil market, higher prices for one type of fuel lead to higher prices for other fuels, O’Donnell said.

Much of that price increase is due to transportation costs, both in pipelines and in trucks that carry propane from pipeline hubs, he said.

Most of the propane used in the Midwest and Great Plains originates in an underground salt cavern in Conway, Kan., which is home to about 30% of the U.S. propane supply.

One pipeline from Kansas into South Dakota is accessible in Wolsey, west of Huron, O’Donnell said. The farther the fuel travels in pipelines, the more it costs wholesalers. Prices go up further as retail distributors truck the fuel around the state and directly to homes, paying more in diesel costs when traveling far to the west or north, he said.

“The further you get away from Kansas, where the pipeline originates, the higher the pipe tariff or the pipeline fee is to load from that terminal,” O’Donnell said. “And not only is the price of the propane going up, the cost of the trucks bringing it to homes is much higher.”

When it comes to retail pricing, cost increases borne by wholesalers and retailers are typically passed on to consumers, O’Donnell said.

But he noted that businesses at all levels of the supply chain like to see low prices for fuel, even if they pass most of the higher per-gallon costs to their customers.

“We hate to see prices go up this high because it’s a natural instinct for people to cut back or look for alternative heating sources,” he said. “We move more gallons when the price is cheaper, so as a wholesaler and a retailer, you want prices lower and more affordable so people aren’t reducing propane use to save money.”