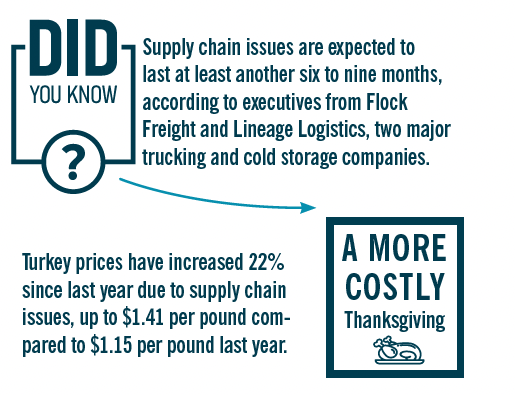

By now, American families are feeling the widespread bottlenecks and crowded ports. Higher prices and limited supplies of certain products like groceries have become commonplace. This year’s Thanksgiving is reported to be the most expensive meal in the history of the holiday. Holiday shoppers are encouraged to buy their gifts early. Shelves that would normally be full now sit empty.

But the problem is nothing new to those in the construction industry, who have been facing more than a year of holdups and frustration, which only seems to be worsening.

Recently, Michael Raby, owner of Raby Construction, a general contractor for commercial and residential projects, prepaid for materials needed for a job, thus locking in the price. It’s the kind of deal he makes all the time. But when the material came due six weeks later, the seller told him the price had gone up.

If the material stops, I don’t have work for the crews. It means guys don’t have paychecks.

-Michael Raby, owner, Raby Construction

“They told us I needed to pay 6% more,” Raby said. “I told them that’s not fair, and they said, ‘You don’t have to take it.’ But of course, we do have to take it. And so we had to pay it even though we ordered it.”

It’s become the norm among builders and general contractors doing business in the middle of a global supply chain crisis.

“We really noticed it probably six months into COVID,” said Charley Patrick, manager of business development with Triangle Construction. “Since then, it’s gotten a lot worse.”

Lead times for nearly every material has increased across the board for most builders and predicting which materials will see the worst delays has become akin to tossing a dart with your eyes closed.

“Here’s one example,” Patrick said. “We had a recent project where we were finishing it, and all we were waiting on were these glass canopies we’d ordered eight or nine months ago. It was extremely difficult to get this glass even though we ordered it with plenty of time. What should’ve taken two months was stretched out that long.”

Products that were never difficult to find — drywall mud, for example, or paint — suddenly became highly-coveted items.

The problem is not unique to the Upstate, or even the United States. The movement of goods around the world is based on a “just-in-time” supply chain, meaning materials ship only as they are needed in the manufacturing process.

“We were very spoiled for a long period of time,” said Jim Sobeck, CEO of New South Construction Supply. “Back in the 1980s, Japan popularized just-in-time instead of just-in-case, in which people used to keep a safety stock.”

Whereas fully stocked warehouses with a surplus “safety stock” of materials would have been common in the supply chain of old, a just-in-time model drastically reduces the need to store excessive materials, due to the synchronized nature of the global chain. The benefits are obvious — costs go down for manufactures, businesses and consumers, and production is more easily adapted on the fly.

“We’re huge in rebar, for example,” Sobeck said, “and once someone asked me, ‘Why do you have so little rebar inventory?’ I told him I can call my supplier in the morning and get it by 2 p.m. that afternoon, so why would I need to keep a three-month’s supply on hand? For years, across the whole industry, this was the norm.”

But that interconnectedness comes with a price, namely, its vulnerability to major upheavals like the pandemic.

“If you have any interruption in that — a natural disaster, or in this case, a pandemic — the supply chain is so lean that it can wreck havoc,” Patrick said.

Now the leanness of that supply chain has left those in the industry weary to trust in its efficiency.

“Do I think people will go back to just-in-time any time soon? I don’t think so,” Sobeck said, whose own company has increased its own inventory by 50%. “There’s a lot of scar tissue right now. I think the old adage ‘once bitten, twice shy’ holds up, as a lot of people who’ve been burned right now are going to be very heavy on inventory for a while.”

For now, local builders can only warn their clients that material is going to take longer to arrive, projects will take longer to complete, and prices are going up.

But if the supply chain remains bottle-necked — something experts warn could stretch into mid-2022 — it’s not just customers who feel the burn.

“If the material stops, I don’t have work for the crews,” Raby said. “It means guys don’t have paychecks. We usually try to offer a lot of overtime hours to keep everybody busy. Right now I could easily add a crew if we could get materials. These are good guys and they’re trying to work. But on some jobs, we’ve got some awful clean equipment that just isn’t being put to use.”